No challenge too big for Clarence Seedorf

No challenge too big for Clarence Seedorf

No challenge too big for Clarence Seedorf

In the gym was Clarence Seedorf, arms still bulging, abs still firm, and yet old enough to be the father of the kids around him. Just off Rio de Janeiro, his favourite city, the 37-year-old would teach the things he learned over the course of his 22-year career. He’d ask them questions. He encouraged them to think for themselves. It was a two-way conversation off the field; orders and lectures saved for the field. They’d talk about positioning, footwork, little details, shaping the body to receive the ball, opening up, preparing for it, moving this way instead of that.

Two in particular — Doria, 19, and Vitinho, 20 — were protégés. Seedorf faced many temptations, but he doesn’t drink alcohol or coffee, and he warned against that kind of bait: going out, drinking, sleeping late. Even on the field, Seedorf managed himself like a gentleman, drawing red cards only twice over the course of hundreds of games. There was this obligation to protect them. One time, as Botafogo broke for the half-time interval, Vitinho stopped to answer a few questions from a reporter. It was one interview too many for Seedorf. He ran over there and cut it short. “Even though we were leading,” he said in an interview with FIFA, “it was a tough game and it was by no means over. It was important to stay focused right to the end.”

All the while he had studied and earned his UEFA A licence and did the same homework as the coaches in the Netherlands. Seedorf went to Boavista, a smaller club in the state, for practices and games, and he coached the 17 year olds. In April he will get his full licence, but even before that he will coach AC Milan. Seedorf is never one to wait.

He cried at the press conference, a tough decision to quit Botafogo, but here was the chance to fly back to Milan. In 2008, he and the Rossoneri discussed what would happen “afterwards.” He and Silvio Berlusconi share a close relationship, and the timing was right. Seedorf would never relegate himself to a lower league, and the challenge is big and difficult — just how he likes it.

This is a man who always wanted one more: one more game, one more repetition, one more European Cup than Frank Rijkaard. Seedorf loved Rijkaard, the philosopher from a generation of total football, the most responsible midfielder Ajax ever produced, and once his coach. “If I was happy with three trophies,” Seedorf told The Guardian, “then suddenly I had to have four. If I was happy with four then I had to have five.” He is a maverick, a communicator and disciplinarian, a singer, poet and thinker. “I would’t like to put myself in a box,” he told the New York Times. “I think you get the full package once you get Clarence Seedorf.”

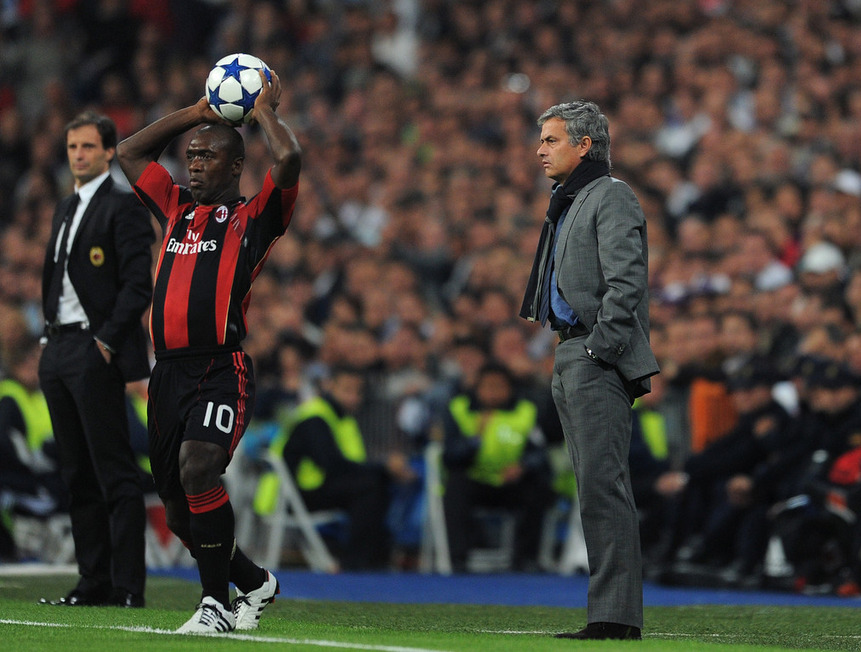

It is more than a coincidence that he will replace the manager that effectively forced him out of Milan. Seedorf didn’t like the way Massimiliano Allegri handled him. In that final year, almost two years ago, he only featured the Dutchman sparingly. “I’d played an average of 48 games a year,” Seedorf said, “and, almost overnight, I started playing half that number.”

Not many can convince him otherwise: Seedorf has immense confidence in his skills. Sometimes he came across cocky, a smart aleck. His own people booed him off the field when he represented the Netherlands, and some don’t care that he’s won the Champions League four times with three different teams. But he was raised to lead. He captained national teams at every level as a kid, playing for Ajax as a 16-year-old, the youngest of anyone in the history of the club. Some asked him to skip a year in school, and he later served as a member of the student council.

One of AC Milan’s sports psychologists said that Seedorf “talked 10% like a player, 70% like a coach and 20% like a general manager.” He continued: “I also saw that he was doing it with a positive intention.” The fact remains: has any footballer made the transition from player to manager so quickly? Maybe that’s just Seedorf. There is hardly a break in between.

He has come to speak six languages. He is the owner of a restaurant in Milan and he invests money and time in the kids of Africa with his charity, Champions for Children. Seedorf wrote for the New York Times, worked as a commentator for the BBC and did a documentary on Robben Island, the prison ground where Nelson Mandela spent 18 years jailed in a cell with a floor for a bed and bucket for a toilet.

There is lots of material about apartheid, and Seedorf had indeed read Playing the Enemy, a book about the national rugby team — for so long an example of white supremacy in South Africa — that Mandela embraced and supported as they won the 1995 World Cup. Seedorf would interview a former prisoner, still scars on his face, but he didn’t want to just hear about his experiences: Seedorf wanted to relive it.

That’s normal for him. He prefers to visit a country, a club, much like a scout, to see things for himself. So he got the tour, and he brought cameras from the BBC. And he let the guide tell the story about his squalor, about the football they played in a field now rife with weeds, about his kids, now grown, who think he is the greatest for what he sacrificed. At one point Seedorf asked why the sport was so important to the people imprisoned for the crime of being black. He has a remarkable presence on television, but Seedorf didn’t dominate the screen or reel off facts and stories he most likely already heard: he let this man speak, and he listened.

Of course, he is only as good as his mentors and those who helped him along the way. The greatest of managers coached him: Fabio Capello, the marshall and professional, so dedicated that he missed his son’s wedding for a friendly; Sven-Goran Eriksson, democratic and compassionate; Carlo Ancelotti, comedic, generous and loyal; Guus Hiddink, the tactician and ultimate evaluator; Marcello Lippi, a former defender and pragmatist; and Louis van Gaal, the teacher and ruthless autocrat. (Not to mention Ajax, the very best academy he joined as an eight-year-old.) Seedorf had the very best education a player could get.

And there is jealousy. Ian Holloway, called the “archetypal British boss” in The Blizzard, looked at Seedorf and compatriot Edgar Davids and marvelled. “I can’t get over how educated they are,” he told the magazine. “They know exactly what they are talking about. They understand football, the formations and the problems teams face. But that just sums up the Dutch for me, and we have to try and educate our lads [in England] to the same standard.”

It didn’t come without struggles. On more than one occasion Seedorf and Capello clashed during their spell together at Real Madrid. Two big personalities who don’t like to compromise. But the Italian was still “one of the most important coaches of my career,” Seedorf told The Guardian. Capello could scream and swear at his players at half-time, and he looked for a fight. “And when he did,” said Seedorf, “the team would go out and kick butt.” It could get tense and hot in the dressing room but Capello fired them up, and later he would pat players on the back or shake their hand. Nothing carried over.

Eriksson, though, was the biggest influence. When Seedorf moved to Sampdoria, he was lost: he didn’t understand Italian tactics in a country where players worked like soldiers running through drills, their heads down and their feet moving. In Holland, he said, they could sit down and discuss and strategize. This was strange. And so Eriksson was not the kind that dictated — he was more of a tutor than a manager. “He explained to me that among a load of bricklayers the work of the architect can go unappreciated,” Seedorf said in an interview with FourFourTwo magazine, “so I had to put a few bricks down.”

And then Milan truly gave him the room to express himself. As a midfielder he played deeper, but he also had the freedom to move forward when he saw an opening and slow the game down as he pleased, and Seedorf could rifle a shot from anywhere outside the box. Muscle wasn’t a problem: He was the perfect athlete. For a few years Rui Costa owned No. 10, but when he left Seedorf took it, and when Ronaldinho arrived, he didn’t give it up. That was his position: the focal point of the midfield, intercepting passes and negotiating ways out of jams, playing almost like a Brazilian.

Maybe that’s what drew him to Botafogo in the first place. He could’ve retired in MLS or China. Instead, Seedorf chose a team in the shadows of Fluminense, the club of the aristocrats, and Corinthians, the biggest in Brazil. He chose a team without a proper stadium and with fans that he himself criticized for their lack of support. It wasn’t that he wanted the obscurity, to live near the beach: he looked for the biggest challenge. He scored eight goals — the highest total of any single season in his career — and he helped Botafogo qualify for the Copa Libertadores for the first time since 1996.

His farewell was tearful, and he cried into the arms of the coach and hugged all of his teammates. The man is worldly, and he’s played in four different countries, but no decision is easy for him. And it doesn’t get easier: AC Milan are seven points out of the relegation zone and 20 out of third place. This team forgot how to win.

Under Allegri, Milan registered eight wins, 15 draws and 16 losses against top-six teams in Serie A since 2010. In Serie A, they’ve won away only once. Through the first five games of the season, Milan posted their worst defensive record since 1984. Before that they made their worst start in 80 years. In the Champions League, away from home, they played frightened, losing six, drawing seven, winning four. Almost every time they would get the lead, they would lose it.

And the frustrating part of it all is that Allegri averaged 1.92 points per game, the second highest total of any manager in the Berlusconi era. They could win, but they just didn’t. They tied games. They once beat Barcelona. Milan did things no one expected and accomplished nothing when expected to do things. Success was an anomaly.

Seedorf knows what it means to be Milan. He has the experience. He is success. He is the second black man to coach in Serie A. He has time to assess the damage and recover for next season. Along with him will come former teammates: Hernan Crespo, a student of the game who studied the origins of tactics, and Jaap Stam, a coach in the Netherlands with a face that could intimidate anybody. But it is Seedorf who is leading the way, as he usually is.

This piece was written by Anthony Lopopolo, a Senior Writer for AFR. Comments below please.