An early exit after 27 years: Sir Alex steps down in his own style

An early exit after 27 years: Sir Alex steps down in his own style

An early exit after 27 years: Sir Alex steps down in his own style

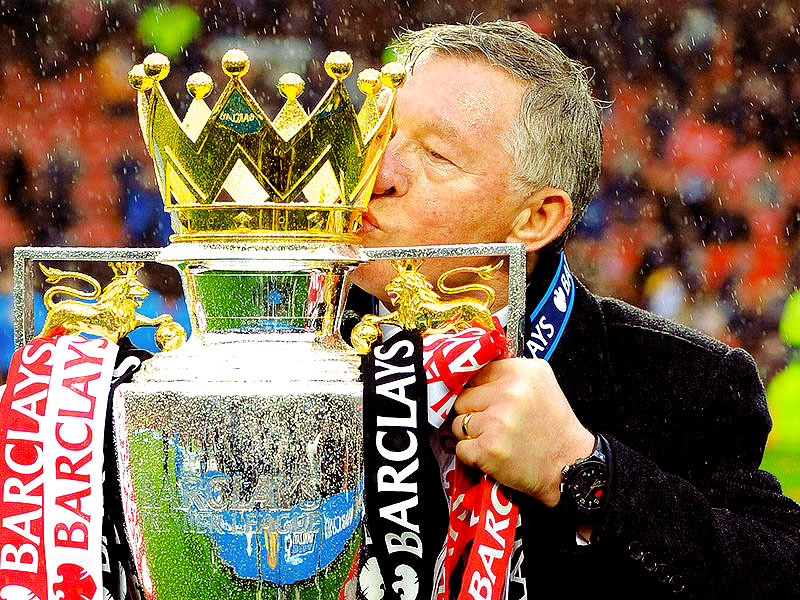

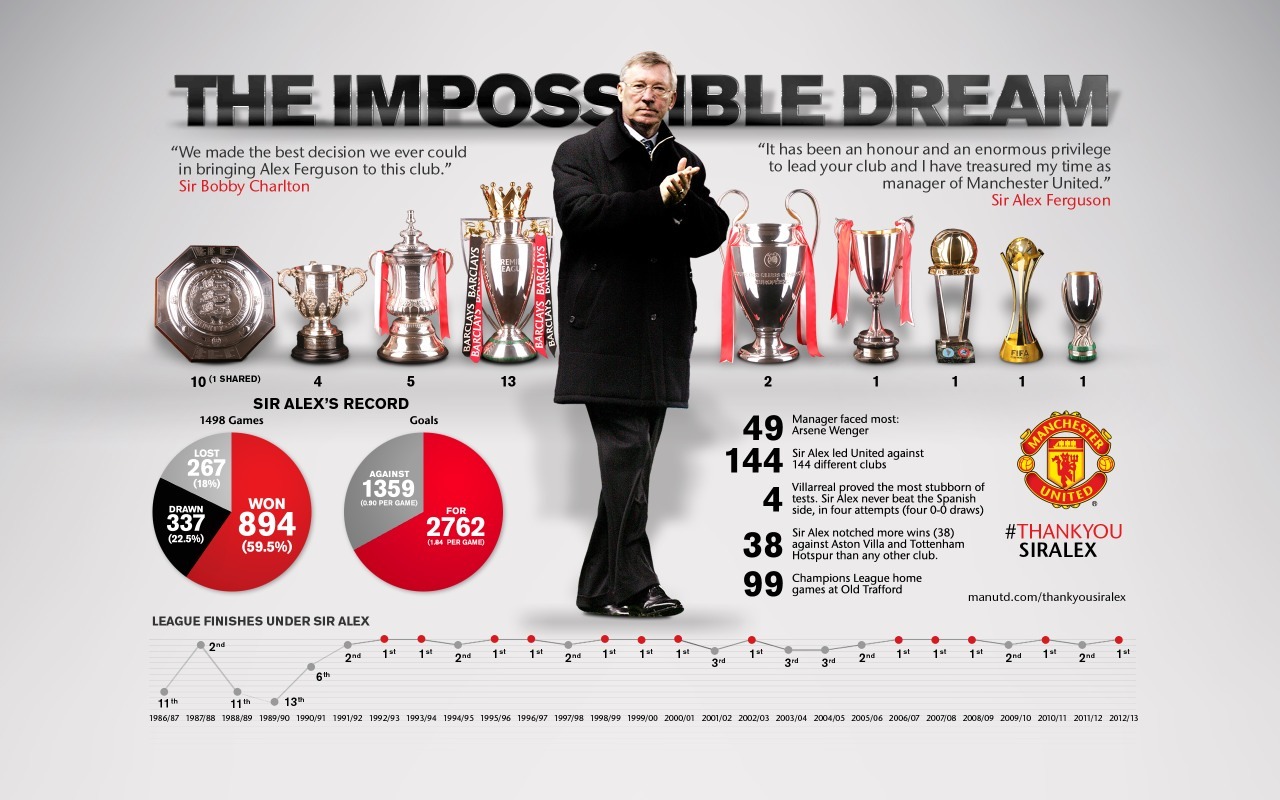

The numbers pop out of his resume like eyes out of a cartoon character: he won 27 major trophies with United over the same number of years; he outlasted 116 managers on seven major European clubs; and he’s won 75% of his home games at Old Trafford. Nothing satisfied his hunger for success, and his diet never consisted of anything but winning. He’s always the first man at Carrington, the team’s training facility in Greater Manchester, there before staff and players as early as 5 a.m. He’s said over and over that he has trouble envisioning life without football. Retirement was something he wasn’t exactly ready for. “Nobody’s getting rid of me,” Sir Alex Ferguson told The Guardian in March.

Nobody – not the media, not the club, not his body – but himself did.

He decided now is the best time to retire; now, at 71 years of age, is the right time “to leave,” as he said in a brief statement on Wednesday, “the organization in the strongest possible shape.” Indeed, he has left the club with its 20th league title, successfully wrangled from the hands of its noisy neighbour, Manchester City.

This time, surely, he wanted to get it right. His initial decision to retire, in 2002, was, in Ferguson’s own words, an “absolute disaster.” His wife, for one, wouldn’t let him. He was sure Cathy would be “fed up” with him around the house. Since then, he’s won 12 more trophies. But this time is different. Yes, he is due for hip surgery this year, and there is a pacemaker to worry about. Sometimes he said his health would be the thing that tells him when to put the game aside; other times, he made sure we understood that “it won’t be a doctor that tells me to quit.”

Sir Alex Ferguson even wrote in a recent match programme that he didn’t have plans “to walk away from what I believe will be something special.” He may be on to something, but he won’t be part of it. Deliberately, he led us astray, all of us following the scent into a trap of deceit. If information is power, then he’s had it. He’s always contradicted himself for effect. If the Italians were the inventors of the smokescreen – “when an Italian tells me it’s pasta on the plate,” Ferguson once said, “I check under the sauce to make sure” – then he is by far their best pupil.

The smokescreen worked. The players have no idea why he’s chosen to retire. Neither do we. “I’ve not got a clue. No one knew about this. It’s a day that no Manchester United fan wanted to come,” former defender Phil Neville told reporters. The media couldn’t tell the difference between truth and fiction, either. To Ferguson, they were supposed to be lemmings, and when they didn’t agree with the message, they got a swift ass-kicking.

Ferguson is a bully. He’s held journalists up against walls, and he’s threatened them. He’s banned them and thrown them out of the club. “We all had numerous bans for writing stories that might be perfectly true, perfectly fair,” Matt Dickinson, chief sports correspondent of the Times, said on the newspaper’s website, “but because they don’t fit Ferguson’s wishes, you’re banished from the club.”

The more power he’s gotten, the more he’s wielded it, abused it, harnessed it. But he worked hard to reach this stage of dominance. He is a winner, but he wasn’t necessarily born one. Not everything was natural. Early in life, he followed his father to work in the shipyards of Scotland, and he drove all over the place. He served an apprenticeship as a tool maker and he played football part-time. Once, he got the chance as an amateur to play against Rangers – his beloved club as a kid – but shied away from the opportunity until his father and manager gave him a whipping. In the game he scored a hat-trick, and a kid who was so defeatist found some strength.

Ferguson did not, however, win any big prize as a player. “But I had this great desire to win,” he said in an old documentary on Scotsport as manager of Aberdeen in 1985. “I think that it’s carried me right into management.” You could say he’s made up for lost time as a manager, winning the things he could not as a player. And there was not, apparently, much time to spare. He made up his mind early to become a manager. “When I got married,” he said in the documentary, “I didn’t go on my honeymoon. I went to coaching school to get my badge.”

There is something else, though, that’s driven him far from defeat: the idea of losing. Gordon Strachan, the current manager of Scotland, called Ferguson the “world’s worst loser.” Oh, he was a bad one. He could throw fits if his team lost. He could also throw parties if they won. The man had swings in emotion that could frighten. And all of his players, from Aberdeen to Manchester, loved him for it. All of them understood that he knew the game better than most managers, but Ferguson worked best as a motivator, a man of action. He could be ruthless – to players and press alike – but many had colossal admiration for him.

He’s always laboured to earn the respect of his players. He never walked into any joint with a sense of entitlement. Before the fame, he served apprenticeships as a manager with East Stirlingshire and St. Mirren. He paid his dues. “He’s a man that wants to learn all the time – no matter where he goes,” Strachan once said.

As a young manager, Ferguson especially found it hard. Some players were older than him. But he kept on going. He achieved something remarkable in 1980: For the first time in 15 years, a team other than Celtic or Rangers had won the Scottish title, and he was there, at 39 years of age, managing that side. “That was the achievement which united us,” he said in The Boss: The Many Sides of Sir Alex Ferguson. “I finally had the players believing in me.”

Of Aberdeen, he thought of the world. Before he was offered a chance to manage Manchester United in 1986, Ferguson had already dismissed a few opportunities to coach abroad – from Wolves, Arsenal and Tottenham – and he did so rather easily. “I didn’t think they were above Aberdeen,” he said. “I didn’t ever think they could match what was here.” It was there, at Aberdeen, where he learned his values as a manager. There, not at Manchester United, did he find the identity of his managerial style. Like a certain Mourinho today, he pitted the media’s words against his team and used them to motivate his players. Ferguson was the mastermind of the siege mentality – a certain inventor of it, really.

We first got to know Ferguson as the ruthless winner. That’s all he allowed us to see. But the roles of nurturer and leader came easiest to him, and he performed them like an actor fit for the job. The Scot had this ability to put you at ease one minute and on the edge of your seat the next. He could be a father figure and a disciplinarian. He had the gift of kindness but also the wrath of an angry judge. The lengths of his personality went far and wide, but he got his toughest test when Eric Cantona, who played brilliantly but sometimes flouted the rules, came to town.

Cantona would arrive late to practice, something otherwise punishable under Ferguson, and leave the day without a word of warning. He kicked a fan, and he wasn’t all that pleasant to deal with. But Cantona was different. He wasn’t normal. One French journalist, Erik Bielderman, said in Cantona: The Rebel Who Would Be King that “Eric can only work with a coach who’ll be a substitute for a father, who will stand by him in public as he would stand by his son, regardless of what he does.”

By his own admission, Cantona needed someone who could empathize with him, someone who could understand the misunderstood. He craved direction. He always wanted to know where he was going, when he was going, why he was going. “I have to be persuaded that a certain path is the right one,” Cantona said in the biography. Directions weren’t his to give. Cantona looked for them, and Ferguson would always be there, ready to give them. As a manager of men, Ferguson did not see the egomaniac portrayed in the press. He did not see the violent lunatic others had interpreted Cantona to be. He saw lots of anguish in Cantona’s eyes. Like a dog, Cantona just wanted to follow someone’s lead. Otherwise, he could go mad, and Ferguson made sure, on a human level, that this Frenchman never lost his leash.

Almost 20 years later, Ferguson still leads the way – with certain pride and loyalty. He knows Manchester United, the team he’s come to love and live and father and coach, inside out. “You know how good you are,” he told the players in a speech after his final game at Old Trafford. “You know the jersey you are wearing and you know what it means. Don’t ever let yourselves down.” He’s called the shots: about the timing of his retirement, the manager succeeding him, and the way forward. David Moyes, the 50-year-old whose time with Everton has been praiseworthy, will take charge of United solely on the recommendation of Ferguson.

But the elder Scotsman will not be too far away. As an ambassador for the club, Ferguson will still be watching over the team he’s cultivated and architected. He will not lose his entire grip on the game that’s come to define his life.

This piece was written by Anthony Lopopolo, a Senior Writer for AFR. You can follow him on twitter @sportscaddy. Comments below please.