As We Watch Brazil’s Dance

As We Watch Brazil’s Dance

As We Watch Brazil’s Dance

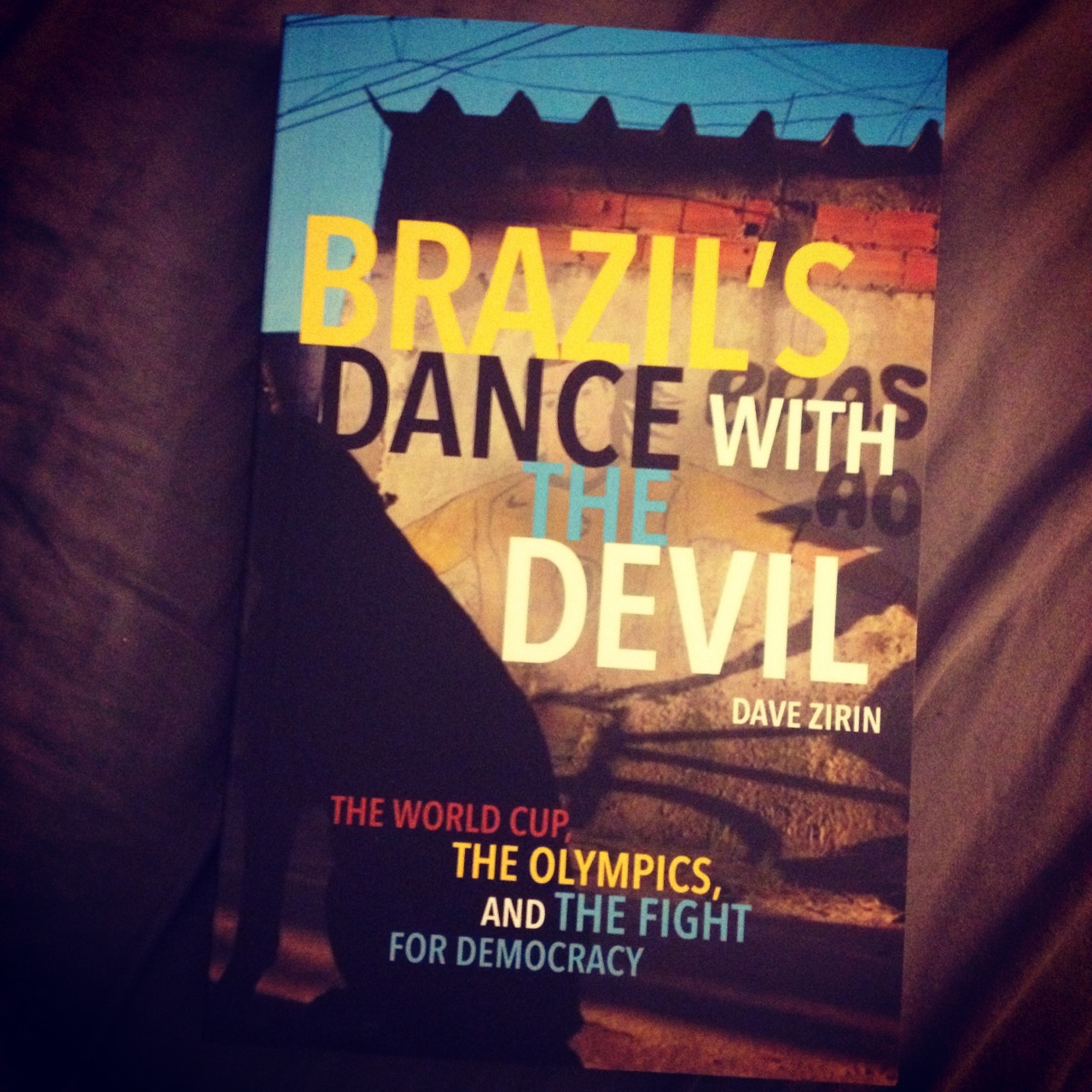

In the beginning of Dave Zirin’s book, Brazil’s Dance with the Devil, one of America’s pre-eminent political sports writers tells us that he simply had to write a book about Brazil – a country, said one of his professors, that is certainly not for “beginners.” But Zirin is no beginner. He is the voice of reason in a country of unreasonable disparity.

He first starts in the favelas, one of them surrounding Rio’s Maracana, where hundreds of homes, once built by generations of families, were “cracked open.” Those residents were relocated, some moved hours away, some getting no compensation at all.

Zirin then interviews journalists and academics, street sweepers and the indigenous peoples, as he searches for the meaning behind everything that has happened in Brazil over the past year. His latest book is an essential companion for this month. It examines what it means to be Brazilian and explains why FIFA is exploiting the land like its colonizers from Portugal so many years ago.

Of course, Zirin also covers the sport of soccer itself. He recounts the stories of the English coming to the shores with balls in their arms and factory workers playing in teams. Zirin writes about Pele, the ultimate professional, and Garrincha, the “angel with bent legs,” and then there is his favourite, the Brazilian Socrates. This soccer legend was a “medical doctor, a musician, an author, a news columnist, a political activist, and a TV pundit,” but most importantly Socrates – “as bold as those national colours,” Zirin writes – fought against the early dictatorship of the 70s and 80s.

Zirin is upset about a lot of things, and he cuts through all the white noise and stereotypes about Brazil. He is angry that the Maracana was shaved down in capacity. Luxury boxes as well as VIP sections were instead added, places where “modern caesars can sit above the crowd.” Many people do not just talk about the games they played at the Maracana in Rio; they remember the numbers of people. Around 220,000 witnessed the tragedy in 1950, when Brazil lost 2-1 to Uruguay in the final. Now the Maracana has a capacity of just 75,000. Geographer Chris Gaffney called it “the death of the crowds.”

Then there was the institutional racism, which is not surprising given that Brazil was the last country to abolish slavery, in 1888. Those of African descent, “the hands and feet of Brazil,” writes Zirin, were given “nothing but freedom.” These people were desperately poor, even if they made up a significant part of the population. Afro-Brazilian footballers were not so welcome in the 1920s and 30s. “Afro-Brazilian players took great pains to make no physical contact whatsoever with their opponents,” writes Zirin, “lest they risk reprisals.” So these descendants of slaves played gracefully and laid the foundations of o jogo bonito – the flicks and feints and flair were all like capoeira, the old warrior dance of the black slaves.

Over the decades the Afro-Brazilians and mulattos and whites would all play together, first for Rio’s Vasco da Gama and then for Brazil. Soccer brought together the immigrants – mostly Italians and Japanese – and the emancipated slaves, and they could all express themselves as uniquely Brazilian. (Zirin references this mosaic of Brazilian society and asks questions about so-called racial democracy in the country.)

Dictatorships that followed also began to use soccer as propaganda and as a mobilizing force. Slowly the sport in Brazil turned into commerce. Zirin is so entrenched in his studies that you can feel his sorrow through his words. Players were eventually exported and sold to European countries much like the gold and rubber in the centuries before. Brazil is still in some ways a vast mine.

Zirin also writes about the Olympics, but at this moment it is his writing on the World Cup that strikes hardest. It is just one of the latest of these mega-events traveling from country to country like a carnival act. “The World Cup is like a marvellous party,” says one youth activist, “but what happens the next day when we’re hung over and the bill comes due?” Zirin not only answers this question in the book but also asks why. There is so much to cover, but he does not waste time with the minutiae of history. This is book he had to write, and it is one we have to read.

This piece was written by Anthony Lopopolo, a Senior Writer for AFR. Comments below please.