The End of Camp Cupcake: The Evolution of the January Friendly

The End of Camp Cupcake: The Evolution of the January Friendly

The End of Camp Cupcake: The Evolution of the January Friendly

By Zack Goldman

The United States Men’s National Team’s January schedule is well-worn conversation in American soccer circles, but it remains a unique and curious phenomenon to the rest of the football world.

Owing to the spring-to-fall schedule in Major League Soccer, the Yanks have traveled to Carson, California for a winter training camp eight of the last 11 years—and every time it’s been roughly the same. A slew of experienced role players and promising youngsters from MLS join up with a handful of regular national teamers also out-of-season to form an experimental side that will never again be cobbled together. At the end of weeks of training, the ragtag group does battle against another nation, usually one who is similarly makeshift and comprised of home-reared talent also on a break between seasons.

The ensuing international fixture between B-level squads (or worse) has resulted in this annual exercise being termed “Camp Cupcake,” a moniker blended with equal parts endearment and disparagement in the collective imagination of American soccer fans and media.

Everything we have come to know about Camp Cupcake, though, seems to have been shattered in manager Jürgen Klinsmann’s inaugural winter holiday.

From the moment the roster and itinerary were released, a new bar had been set. The best and brightest of US-based talent, including a score of players who lifted the Stars and Stripes to a World Cup place, were called up—and the group was to take a two-week excursion to Brazil mid-camp as a dry run for this summer’s tournament. This was definitively not your father’s Camp Cupcake—nor that of former managers Bruce Arena or Bob Bradley, the baked goods enthusiasts they were.

Even in previous World Cup years, the January camp functioned as much more of a longitudinal exercise designed to spotlight young talent or to offer last chances to dance with aging veterans. Klinsmann’s edition, by comparison, appeared far more pointed from the get-go, sharply focused on identifying domestic players capable of earning one of 23 plane tickets for this summer’s showpiece, and nothing beyond.

Along that train of thought, the greenest invitees to camp were, by and large, linked with positional question marks or spots of outright vulnerability in the national set-up, like left back. Even then, top MLS prospects Seth Sinovic and Chris Klute were let go part-way through, and the only other option initially brought in, Portland Timbers standout Michael Harrington, didn’t even dress for the Korea match.

The message a week before the friendly was clear enough: This was not to be a month-long recreational experience with the party favor of a cap, but rather a purposeful fact-finding mission. Where previous USMNT managers have approached January as a free chance to take shots in the dark, Klinsmann used it as an opportunity for target practice. Where others have put out a net, Klinsmann opted for a funnel. It is fitting for a man whose trademark has become his conical focus, his proclivity—nay, insistence—on publicly referencing the idea of a “depth chart” and “competition for places” that this camp would evolve into such a targeted and serious combine that stands in opposition to its past reputation.

The match against Korea drove that cultural shift home even more forcefully. While the team sheet was missing names like Michael Bradley, Clint Dempsey, and Jozy Altidore, it featured a first-choice center back partnership in Omar Gonzalez and Matt Besler, a breakout star of the qualifying cycle in Graham Zusi, and the all-time goals and assists leader in Landon Donovan. What has in the past often resembled an almost rudderless individual showcase of promising freshmen and JV veterans, this time turned into a clear audition to fit into the interstices of a team. The match had an intensity, a competitive spirit, and a heightened sense of purpose usually lacking in ordinary friendlies, much less these ones in the Southern California winter.

It was clear in the big stakes experiments all over the pitch from the opening whistle. Klinsmann inserted Michael Parkhurst, a late-camp call-up ordinarily positioned at right or center back, as the left-most member of the defensive line. Chris Wondolowski, finally beginning to replicate his goalscoring prowess with the San Jose Earthquakes in a US shirt, started up top. Donovan, considered the American captain-in-waiting for so much of his career, was handed the armband.

Aside from matters of selection, the team—in the words of silver-tongued Bruce Arena once upon a time—“tried shit” on a tactical level. Donovan and Wondolowski—arguably the two best off-the-ball movers in the US player pool—clearly and ceaselessly switched positions as the center forward and withdrawn striker throughout the first half, providing a handful for the Korean center backs and a shift from Klinsmann’s more regular target presence up top. Other trials were simultaneously carried out across the pitch: Mix Diskerud was dropped deeper than usual, slotting between the front four and the holding anchor, Kyle Beckerman; the United States’ long-documented use of a high, ball-carrying left back was reversed for long stretches to the right flank; and, the famously one-footed, wide midfielder Brad Davis was tucked inside at times. There was no hockey-style shift change at halftime; in fact, there wasn’t a single substitution until the hour mark. This was more than Bruce Arena’s half-hearted gambles on Richard Mulrooney. This was serious.

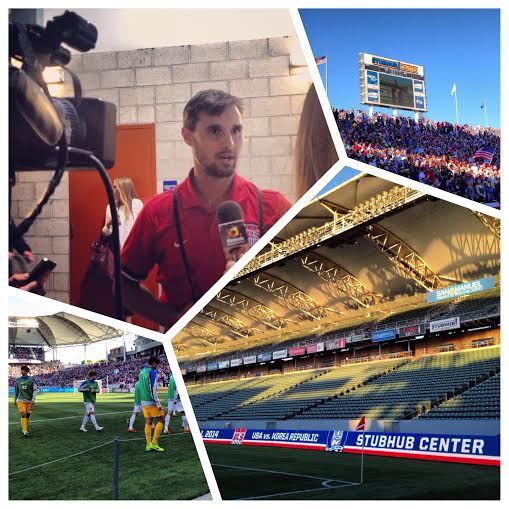

That evolution on the pitch was accompanied by an analogous movement in the stands. While these games in previous years have seldom produced an atmosphere resembling anything close to a typical USMNT fixture—usually featuring a good quarter of the StubHub Center fenced off, with the other three left with a considerable amount of elbow-room—this edition felt in many ways akin to a World Cup Qualifier. I found myself awash in a comforting sea of red-and-white striped kits and Springsteen bandanas, engulfed by hopeful chatter about Gedion Zelalem and Julian Green, and swallowed whole by the chants of the American Outlaws that, to my great surprise, revved the vocal engines of the rest of the capacity crowd—a crowd that, by the way, was heavily pro-US in a metropolitan area that houses the most Koreans outside of Asia. If you closed your eyes for moments, you were in Columbus or Portland or Seattle. Well, maybe not Seattle.

When it was all said and done, the United States prevailed, 2-0, with both goals from Wondolowski, a poacher famous for inspiring frustration and admiration in equal measure. For a soccer culture that delights in having a national team emblematic of a culturally-resonant “never-say-die” attitude, there was no more fitting success story on Saturday than that of the indefatigable Wondo—and it was one that was wholly appreciated by the fans, even behind enemy lines at the home of the LA Galaxy.

The narrative surrounding this match, true to a January camp, remained firmly entrenched in an experimental mystique; but, at least for this year, it made the leap from science fair to laboratory-standard. Though the logic on the field may change slightly in future years without the drive for World Cup places, it seems this fixture has graduated to a new context, both competitively and culturally. And in a cycle that has been defined by so many positive benchmarks on the pitch and in the stands for US Soccer, changing the face of Camp Cupcake is one of them, however small.

This article was written by AFR Contributing Editor, Zack Goldman. Expect to see hear more from him as we get closer to kick off in Rio.