What do we know about concussions? Not enough.

What do we know about concussions? Not enough.

What do we know about concussions? Not enough.

Arsene Wenger did the math for us. “You have only one life,” Arsenal’s manager told reporters, “and you have 60 games per year.” He was here before, just weeks before. Midfielder Mathieu Flamini clashed heads with a defender and collapsed on the pitch. That time, Wenger did not hesitate to take Flamini out of the game. This time, the doctors didn’t tell him anything about Wojciech Szczesny. They needed just 82 seconds to check his signs and ask the relevant questions: Where are we right now? Who scored last? Which half is it?

The Arsenal goalkeeper had fallen down, seemingly unconscious, lying on the ground with his hands up. This time, Wenger’s player pushed on – Szczesny made some more saves and looked fine, a victory alone even in a game that Arsenal lost to Manchester United.

Doctors say there is no average: Every case is different. Minutes later, Nemanja Vidic, United’s captain, smacked his head against his own goalkeeper’s thigh. This was worse. As he fell to the ground, Vidic looked glassy-eyed, a vacant look on his face. He wobbled off the field, left for the hospital, and on Monday he was released.

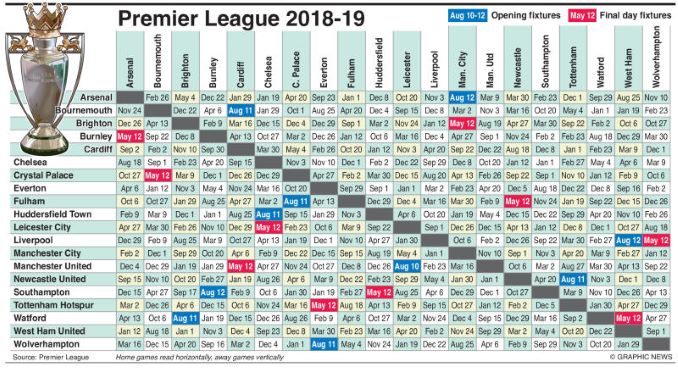

The earliest Vidic can play is November 24. By virtue of his club’s schedule, he will automatically get to sit out at least five days – the minimum for any player concussed in the Premier League. But the waiting could last. We just don’t know how long.

And this was just the latest incident in England, if handled a little better. Only last week, Hugo Lloris, the Tottenham goalkeeper, took a knee to the face. The whiplash was violent: The head snapped back, and he was out. Minutes passed before he got up, and when he was told he had to go off, Lloris looked like a man insulted. The manager, Andre Villas-Boas, liked what he saw, the determination and the fight to stay in the game, and so Lloris remained, and he made a couple more saves.

“The call always belongs to me,” said Villas-Boas. He wasn’t immediately given signs from the doctors that indicted Lloris could continue, and yet he did. Villas-Boas didn’t even heed the weak rules already in place: That a player knocked unconscious should not play that same day.

It seems like an epidemic. Concussions make up 11% of injuries in football, or at least that’s the finding in last year’s British Journal of Sports Medicine. An average of one player per squad takes a hit to the head every month. It’s happening a lot more at the highest level, and more than 50% of clubs in England don’t follow the guidelines. They are talking about it, at meetings between FIFA, the International Ice Hockey Federation, the International Olympic Committee and the NFL. But are they doing enough?

The dots are waiting to be connected with things like depression and ALS and the loss of memory. Now is the time to start paying attention.

The inconsistent truth

It was not the first time this happened to a player of Villas-Boas. In September 2011, while coaching Chelsea, the manager watched as his star, Didier Drogba, clashed with a goalkeeper, losing consciousness in the air, falling down hard, stiff and motionless. It was accidental and innocent, but it was a spectacular incident. Then he just lay there, almost looking dead, the wreckage of a high-powered collision.

“I was scared,” Drogba later told the Sun. “I was lucky to be alive. I’ve had some injuries before – I’ve broken a leg and an arm – but this was worse. I couldn’t cope with the noise. It was too noisy in my head.”

Even though Drogba was discharged from the hospital that same evening with a “mild” concussion, he felt the effects weeks later: The dizziness, the headaches. He even underwent a scan, and the doctors said everything was OK. Something wasn’t right. He missed a month of action. He couldn’t fly. But he did eventually start to score again, and Chelsea won the Champions League, and nothing else was said about it again.

Taylor Twellman is keeping that conversation going. He was, in the words of Sports Illustrated’s Grant Wahl, the kind of player who “threw his head at balls in the penalty box with the force of a bird smacking into a window.” He was an MLS all-star. He was taught to “give ‘em hell.” He scored 101 goals in eight years with New England Revolution.

Twellman racked up another impressive stat, suffering five concussions. The last one, in 2008, knocked his career to the canvas for good.

Always first, Twellman raced into the box and thrust his head at the ball. The goalkeeper ran out and punched him in the head, but not before Twellman bashed the ball toward and into the net. The celebration began with a sprint to the touchline, followed by a punch in the air, but slowly all the joy died. With a bloody cheek, he hunched over and tried to walk, only to fall to the ground in a heap, like someone feeling faint.

The team’s trainer thought he was fine. He could count, he could remember the score of the game, he knew where he was and, most importantly, who he was. So Twellman played that same game, and he took another shot and began to celebrate. The ball went five feet wide of the goal, but he saw two nets. He thought he scored. In this state, Twellman was allowed to play. He was cleared. Some thought he should sue. But there were greater things to worry about. “My head was as soft as a sponge,” he said. “I knew I was done.”

It all set into motion a pattern of absolute agony: Lots of time spent in a dark room, away from the light, unable to read or watch TV or drive or walk his dog. Then came the headaches, the nausea almost every day for two years. He tried acupuncture and antidepressants. Nothing worked. “I sobbed a lot,” Twellman told the Boston Globe in 2011. “When I would cry, and literally let it out from the deepest part of you, I’d fall asleep. I knew I could cry myself to sleep.” He played through pain before – through hernias and broken bones. But the mind does not heal like a broken bone. It is fragile, and in some cases it never returns to normal.

Even if he felt all alone, looking for a doctor to diagnose him properly, Twellman had company. Briana Scurry, a fellow American and a World Cup-winning goalkeeper, suffered a career-ending concussion a couple of years later, while playing for Washington’s team in Women’s Professional Soccer. An onrushing striker kneed Scurry in the temple, and she fell dazed. She remembers, in an article for the Washington Post, the referee telling her to get up. Now. Scurry, too, played on, until she wobbled out of the game for good. The symptoms followed, and the life of painkillers, muscle relaxants and Ambien became hers.

“She came to organize her life around naps and walks, first around the park near her apartment in Englishtown, N.J., and then in Washington, where she moved closer to her doctors,” writes Caitlin Dewey in the Post. “The walks became the only highlights in a lonely, unchanging schedule.” She walked slowly, lapped regularly by joggers who “could never have guessed this woman had won two gold medals.”

It’s not a happy way to depart from a career of distinction. Once upon a time it was heroic, players giving up their bodies to score or save a goal. Nat Lofthouse, one of England’s greatest strikers, was named the Lion of Vienna after he scored the winner for his country against Austria in 1952. No one could stop him: He was hauled down, tackled from behind, elbowed and duly knocked unconscious. He was thought to be a brave lad, and he was lionized for it, and, really, he managed to live a long life after all that.

‘If there is any doubt, keep the player out’

It sounds nice, doesn’t it? FIFA’s motto about concussions is clear: “If there is any doubt, keep the player out.” But it’s not exactly precise. There is no strict rule for clubs across the globe to follow. It’s not standardized, just encouraged, recommended, put forward. It’s advice.

So the doctors are speaking up. They’re not telling us to stop playing sports. They want to educate us. Specialists remind us that soccer is one of the most dangerous sports. Studies show that players who head the ball frequently could lose bits of their memory, even develop neurological disorders or abnormalities in their brain. But specifically, they want to keep athletes far away from the field of play after they’ve suffered a blow to the head.

“They can’t safely work out or play,” Dr. Robert Cantu, a concussions expert at Boston University, told Sports Illustrated in 2010, “and if they try to do that they’ll aggravate their condition almost certainly, and that could decide whether they ever come back in the future.”

Drogba felt the effects weeks after his incident; Twellman years down the road. And Scurry had to undergo surgery to diffuse the headaches she could no longer tolerate.

Yet, some of them play on. Look at Romelu Lukaku’s story: In his debut with Everton, he barged his way past the defenders and scored his first goal for the club with his head – it was glorious, an immediate message sent to his old manager, Chelsea’s Jose Mourinho – but not before the goalkeeper crashed into him. “I didn’t even know that I scored,” Lukaku later said. “That was the first thing that I asked. I don’t remember anything.” He almost scored another, minutes after losing consciousness.

If a player takes another hit to the head, it could even possibly kill them. “If you have another concussion … it can cause a disproportionate amount of damage” Dr. Adam Hampshire, a senior lecturer in restorative neuroscience at Imperial College in London, writes in The Independent. “There is also the danger that you will not be performing at 100% in a concussed state. If you’re not at your best, in a contact sport, the chances of making a mistake and getting injured again must be higher.”

Broken noses, headaches and lingering questions

This issue is nothing like the legal battle between the NFL and its former players. The league recently agreed to pay US$765-million to settle a dispute with 4,500 players, who claim they participated in the sport without knowledge of all its dangers. Current and former players are committing suicide. It’s ugly.

In European football, there is no conspiracy to hide. Here, men weighing 300 pounds don’t slam into each other, head-first. The incidents here are purely accidental, collisions born out of a chase for a ball or a pursuit of a goal. And the medics who handle these players are not incompetent. The same doctor and physiotherapist that treated Lloris had helped to save the life of Fabrice Muamba, the former Bolton midfielder, when he collapsed on the pitch at White Hart Lane last year.

Maybe there is just a different sense of safety in North America, where kids can hardly play a sport without supervision. Maybe North Americans see things differently. Or maybe the managers in Europe just don’t understand the severity of these injuries.

Maybe players do know better. They get worried. They wave frantically to the sideline, with panic in their eyes. The ones who’ve suffered the blow are the ones that don’t know what’s happened. “When he has been knocked unconscious,” FIFA’s medical chief, Jiri Dvorak, said, “the player himself may not see the reality.”

One time, in a friendly between England and the Netherlands last year, Dutch striker Klaas-Jan Huntelaar clashed heads with a defender. It was his second concussion. He jumped for the ball, taking off like a rocket, and powered the ball into the net with his noggin. But he was left on the pitch, frozen, grass in his mouth, dazed. “When I cough I feel my brain is still shaking,” he told reporters the day after the match. “I have a headache, swollen and blue nose, and a concussion. I did not know I had gone off the field – and certainly not that I quarrelled with the doctor about whether or not to play. That was irresponsible.”

So maybe the players have learned. Maybe we have. In MLS, where Twellman was so recklessly allowed to play, a game no longer goes by without a neuropsychologist on the sideline. All players must be symptom-free if they are to return.

But we’re still unsure of the consequences. A study in Italy determined that 51 professional and amateur footballers in the peninsula died from ALS, developed over the past five decades. Stefano Borgonovo, who scored the goal that earned AC Milan a spot in 1990 European Cup final, died this year of the disease. We can’t be sure what caused the onset of ALS in these Italian footballers, and that is the greater point. We just don’t know enough.

This piece was written by Anthony Lopopolo, a Senior Writer at AFR. You can follow him on twitter at @sportscaddy. Comments below please.