New York City and the Rebirth of Supporter Culture: At Home and Abroad

New York City and the Rebirth of Supporter Culture: At Home and Abroad

New York City and the Rebirth of Supporter Culture: At Home and Abroad

Throughout this week, we’ve covered a variety of topics relating to the rebirth of support culture in New York City, from the roadblocks that early supporters had to overcome, to the figures who promoted growth, to the ways that support groups can impact life outside of the turnstiles. Today’s topic? The ways that supporter groups help expats reconnect with their homelands while helping Americans build connections abroad. Here’s Jonathan Williamson.

Leaving truculent traditions of fandom back home is not as easy for other fans. Harnan Amorini, 36, is a member of River Plate New York, the supporters club of Buenos Aires-based River Plate. He moved from Argentina to Queens when he was 13. Twenty-three years in the U.S. haven’t diluted his heavy Argentinian accent, or his disdain for River Plate’s rivals, Boca Juniors.

“I hate them,” said Amorini. “That’s why we try to keep separated to avoid any type of altercation.”

According to Amorini, it would be unlikely for River Plate and Boca Juniors fans to co-exist at any bar in the world, even one in New York City. But his vitriol for Boca Juniors belies an otherwise gregarious nature and omnipresent smile. On a Sunday night in February at The Football Factory, he wore a tight red River Plate jersey while sipping a Paulaner Hefeweizen and discussing what the team means to him.

“It forms your identity,” he said. “I’ve been a fan forever, I mean a crazy, crazy River Plate fan.”

In 2011, Amorini’s devotion was tested. River Plate was demoted to Argentina’s B Division for the first time in the club’s 110-year history. Amorini said the experience was as emotionally challenging as his father’s death. In fact, his coping mechanisms were similar to those of someone who has lost a loved one. He got a tattoo, a shield with the letters CARP (Club Atletico River Plate), on his left shoulder in a show of devotion. He also joined River Plate New York, a support group of sorts.

“It’s a sense of community. It’s a family,” Amorini said. “We have a hardcore group. All these guys are hardcore.”

River Plate’s stint in the lower division only lasted one season. The club won a place back in the top league in 2012. By joining River Plate New York, Amorini made a group of friends who connect him to his home country and a team he loves. While the club reminds him of Argentina, he’s quick to point out the New York City soccer scene is no longer just about traditional soccer hotspots.

“It’s not just European or Latin American people liking it. It’s also everyone else,” Amorini said.

Among the “everyone else:” Americans, most of whom are first-generation soccer fans. Because Americans rarely inherit their teams from family, they’re forced to choose from thousands of miles away. It’s a selection process ranging from impulsive to meticulous.

An amalgamation of family, music and atmosphere sparked 34-year-old Kurtis Powers’ Arsenal Football Club infatuation. Powers was born and raised in Virginia Beach, Va. Like most American children in the 80s, he followed American football, baseball and basketball. But Powers also grew up aware of professional soccer thanks to Arsenal-loving aunts and uncles living in Northeast London. Despite minimal exposure to the sport, he absorbed what lessons he could. From a young age, his relatives taught him that any good Arsenal fan disdains the team’s north London rival, Tottenham Hotspur, commonly known as Spurs. Powers carried the lesson across the Atlantic, but found it difficult to put into practice in the U.S.

“Because I didn’t necessarily know really what Spurs were, I hated the San Antonio Spurs,” he said.

As a teenager, music sprouted the soccer seeds planted years earlier. In 1992, one of Powers’ favorite artists, Morrissey, released the album “Your Arsenal.”

“It identified that name that I was familiar with and I told myself, ‘I’m going to be an Arsenal fan,’” he said.

Soccer’s musical ties weren’t enough to make up for lack of availability. With only one or two televised games a year, Powers remained a casual fan, watching Arsenal when he could. That changed in the 1997-1998 season during which Powers recalls watching around 10 games. It was enough to morph his Arsenal affinity into obsession. Watching consistently, Powers became entranced by the game’s quick pace, atmosphere, and two legendary Arsenal players: Ian Wright and Dennis Bergkamp.

“Maybe it’s because you can see them; they’re not covered in pads and helmets,” said Powers. “Seeing the players, seeing the enthusiasm when they’d score goals, just seeing the support and the singing. It just felt like something so different and better than anything else, and it didn’t stop.”

From that point on, Powers ensconced himself in all things Arsenal. In 1998, he made his first pilgrimage to London to watch the team play. While Powers was all-in for Arsenal, he had trouble finding Americans who shared his zeal. During stints in the Washington, D.C.-area and Orange County, Calif. in the late 1990s and early 2000s, he was unable to find fellow groups of supporters.

Even during his first three years in New York City, where he moved in 2003 to study at the Fashion Institute of Technology, Powers struggled to find fans. One day in May 2006, shortly before Arsenal played Barcelona in the Champions League Final, he saw a man donning a Kolo Toure Arsenal jersey at the Chase Bank on Sixth Avenue and West 23rd Street.

“At that point, he was the first person I’d seen in New York wearing anything Arsenal, so I went up and talked to him,” said Powers.

The man told Powers that a group of Arsenal supporters watched together at Nevada Smiths. Without knowing a soul, Powers went to the bar and watched his team lose 2-1 to Barcelona. He was instantly hooked on what he called “New York City pub culture.”

Almost seven years later, on a relatively mild January morning just past 10, Powers stood outside Blind Pig on East 14th Street. He wore jeans, a red cardigan, a natty black Kangol cap and a weekend’s worth of dark stubble on his face. His deep-set eyes shifted to the line of people waiting outside as he dragged what was left of his cigarette. He finished the smoke, walked to the front of the line, glided past the bouncer, through the door and into a sea of 350 people, members of the NYC Arsenal Supporters Club. Powers founded the club less than two years after watching the Champions League final.

“It is as close to a match day experience as you’re going to have on this side of the Atlantic,” said Powers.

In about 10 minutes, the Arsenal Manchester City game would kick off. Already, the crush of people standing on Blind Pig’s wood-planked floors made it impossible to move without contortions. The fans stared anxiously at one of the 11 massive televisions on the brick walls. For the next two hours, they would sing, cheer and drink. But to the crowd’s dismay, Arsenal lost 2-0. Powers was upset by the team’s performance but took solace in NYC Arsenal Supporters Club’s showing. Not only did supporters pack Blind Pig, Powers said they also filled O’Hanlon’s, another bar about a block down East 14th Street. He estimated the crowd totaled 600 people.

“It’s amazing that on a Sunday morning at 11 o’clock in New York we packed two pubs,” he said.

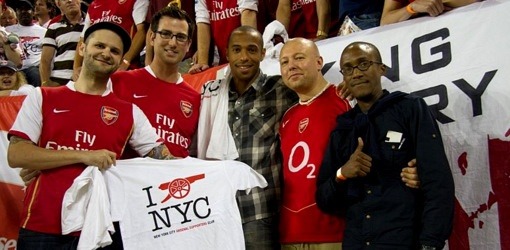

Powers, an advertising agency art director, has been determined to create this type of atmosphere since founding the club in 2008 at Nevada Smiths. In 2010, Powers and Arsenal NYC Supporters Club decided they wanted a bar of their own. Powers said being the only team at a bar helps foster a better sense of community among the club. Arsenal NYC Supporters Club now hosts movie nights, charity events and arranges soccer-related outings, like a meet-and-greet with Thierry Henry, a former Arsenal great now playing for Major League Soccer’s New York Red Bulls.

“Our goal was to create that community,” said Powers. “Have people get to know each other. You’re not just showing up, watching a game and then leaving, but you don’t not want to be here on the weekend because your friends are here.”

Powers prides NYC Arsenal Supporters Club on its inclusivity. You don’t have to be an expat or lifelong Arsenal fan to belong. He hopes the club can serve as an introduction to soccer, and a sporting culture still unique to many Americans.

“You’re introducing people to something that they may never have experienced before. And the support is much different than what I call ‘the passive fandom of American sports’ where you’re more a spectator,” he said.

Powers is quick to refute the idea that inclusivity and a large number of American supporters undermines the club’s soccer street cred.

“You’ll get the occasional straggler Brit that’s on holiday. All of a sudden Arsenal is theirs and they want to know why the fuck you’re into it,” said Powers. “It’s completely annoying to me.”

Powers is determined to dispel the notion of American soccer fans as uninformed, inauthentic and apathetic. He has been to more than 25 Arsenal games in person, talks about soccer with a disarming passion, and even has two Arsenal tattoos on his right arm. One is the club’s logo, a 19th century canon. The other: an ornate “A” and “C” that comprised Arsenal’s logo in the 1930s.

Powers believes NYC Arsenal Supporters Club establishes its legitimacy through massive game day turnouts and an overwhelming presence online. NYC Arsenal Supporters Club has about 9,600 likes on Facebook, more than 6,500 followers on Twitter, a YouTube channel and a blog. Social media not only helps the club accrue new members, it puts Blind Pig on the map of any Arsenal fan visiting New York City from abroad. Powers said they regularly host Arsenal fans from around the world vacationing in New York City.

Be sure to check in tomorrow, as well as the rest of the week, for more on the rebirth of supporter culture in New York City. Tomorrow’s topic? The way that technology drives growth among supporter groups. Jonathan Williamson is a recent graduate of Columbia’s School of Journalism, and you can follow him on Twitter at @JonoWilly. Comments below please.