New York City and the Rebirth of Supporter Culture: Changing Lives

New York City and the Rebirth of Supporter Culture: Changing Lives

New York City and the Rebirth of Supporter Culture: Changing Lives

Over the last few days, we’ve moved from the early struggles facing supporters in New York City to the figures responsible for developing safe havens for fans. Today, we focus on the impact that supporter groups can have on an individual’s life outside of the turnstiles. Here’s Jonathan Williamson.

Mike Neat is one of the founders of the New York Blues, London-based Chelsea’s official New York City supporters club. Neat moved from London to Long Island with his family in December 1978 when he was 15. Neat’s transatlantic love affair with Chelsea didn’t dissipate, despite the challenges created by American media’s lack of soccer coverage in the late 70s and 80s.

“It was horrendous, following the newspapers, trying to get the scores,” said Neat. “I’d always buy the Sunday New York Times on a Saturday night just to get the results.”

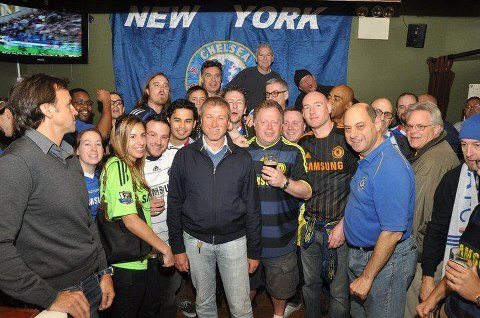

When games finally started finding their way onto television, Neat and a handful of other Chelsea fans watched at various locations in the city and Hoboken. In 1998, a friend recommended Nevada Smiths to Neat and his brother, Steve. The Neats emailed all of the Chelsea fans they’d met in New York City throughout the years, and the New York Blues was born.

“We were able to find a bar that was football only. It wasn’t rugby. It was football only,” said Neat. “Jack welcomed us with open arms.”

In 2010, Keane left Nevada Smiths to pursue a new challenge. When the pied piper of New York City soccer landed just a short trip up Fifth Avenue at The Football Factory, most supporters clubs followed. Because soccer still exists on the fringes of the American mainstream, fans take solace in watching together, regardless of which team they cheer for.

“The common bond between football supporters here is the game,” said Keane.

PSG Club NYC president and founder Julian Stein, 27, cited the sense of community among supporters clubs as “one of the main reasons” to watch games at The Football Factory. For PSG Club NYC, the soccer solidarity translates into more than buying the occasional beer for an opposing team’s fan. In July 2012, Paris Saint-Germain played Chelsea at Yankee Stadium in an exhibition game. The day before the game, PSG Club NYC played the New York Blues in a game at Chelsea Piers. The game, which took on the moniker “The Friendship Cup,” was less about competition and more about camaraderie, according to Stein.

“It was a great way to get everyone together before the big day,” he said.

While New York City’s soccer scene is relatively peaceful, bad blood can exist, according to Keane. He estimates a “skirmish” breaks out about once a month at The Football Factory.

“I’ve had to jump over bar counters and get in people’s in faces,” said Keane. “People just are drinking a lot, and getting a little carried away.”

But in his 20 years behind the bar in New York City, Keane said he’s never seen a major incident that could be classified as anything close to hooliganism. He attributes that to fans putting the common good of the game before their own interests.

“Certainly you will find that the common bond of the game is what gets fans together that wouldn’t be together certainly back in their own countries,” said Keane.

In at least one case, the benevolence of New York City’s soccer scene helped a fan overcome his violent past. Mark Barry is a vociferous Manchester United fan. He’s a member of The New York Reds, the team’s supporters club. Barry is one of the club’s organizers, posting information about watch parties on its Facebook page. It’s also evident to anyone watching a game with The New York Reds that Barry is a spiritual leader. During matches, the 33-year-old pours every ounce of his sturdy 5’6” frame into songs, chants, encouragement and the occasional expletive. One arm is frequently wrapped around a fellow Red, the other clutching a screwdriver, Barry’s drink of choice. But Barry’s passion for Manchester United didn’t always manifest itself positively. He credits The New York Reds with helping him move past a violent incident at a Manchester United game that landed him in prison for six months.

The New York Reds is one of the larger and older supporters clubs in the city. Established in the mid-90s at Nevada Smiths, the club now boasts about 100 regular members who watch at both The Football Factory and Smithfield. The New York Reds doesn’t require a membership fee, has no formal leadership structure and isn’t officially connected to Manchester United’s front office. Despite its amorphousness, categorizing the group as a mere hobby would be unjust.

“If you’re here from somewhere else, this is your family away from your family,” said Barry.

The New York Reds membership is a composite of careers and cultures. Wall Street executives, college students, construction workers, a gay couple and fans from around the world proudly call themselves members.

“I don’t know a supporters club as diverse as we are,” said Barry. “We’re the melting pot within the melting pot.”

Barry’s Manchester United roots are wrapped around his family tree. He grew up in Limerick, a city of 56,000 in western Ireland. He went to his first Manchester United game in 1983 at the age of five with his cousins. He was hooked immediately. By the time he was 16, Barry made the trip from Limerick to Manchester regularly. It’s a trip that entailed buses, trains and a ferry across the Irish Sea. And that’s just when Manchester United played at home. Barry often traveled to away games, making the trip to cities across England and Europe to see the team play. During the 1998-1999 season, Barry said he only missed two of Manchester United’s more than 60 games.

In 2003, Barry’s devotion brought him to Leeds, England to watch Manchester United play Leeds United. He was one of about 400 Manchester United fans in the stadium. As they were leaving after the game, a brawl erupted with a group of Leeds fans.

“A guy came at me,” said Barry. “I just side-stepped him and he went down. I actually hit him on the way down, but I think his gravity took him down.”

Barry estimated the Leeds fan was eight inches taller and significantly thicker than him.

“When you see that you’re out matched, what happens when someone goes down at your feet? I did what I had to do. I made sure he didn’t get up.”

Barry said he kicked the Leeds fan in the head before order was eventually restored. Six months later, police arrived at Barry’s door. The brawl was caught on tape, and he was arrested. Barry was sentenced to a year in prison, and banned from every soccer stadium in Britain for five years.

“After that happened, I decided that I was done. Not done with United. Just putting yourself in situations that you should not be in just for the fucking adrenaline rush,” said Barry.

He was released after completing six months of the one-year sentence. One month after his release, Barry left Ireland for the U.S. He lived in Florida for a year before moving to New York City. When he arrived, he hooked up with The New York Reds almost immediately. Barry – who now works construction and plans to begin studying evolutionary biology and philosophy of science at Hunter College this fall – said the club helps him harness his passion for the team he loves.

“It’s fantastic to be able to go somewhere on the weekends and get your fix, and get all that’s best out of it, and none of the bad,” said Barry.

Be sure to check back in tomorrow, and the rest of the week for that matter, for more on the rebirth of supporter culture in New York City. Tomorrow’s topic? The way supporter groups help expats connect with their homelands, as well connecting Americans to teams abroad. Jonathan Williamson is a recent graduate of Columbia’s School of Journalism, and you can follow him on Twitter at @JonoWilly. Comments below please.