David Beckham, conquerer of nations, retires

David Beckham, conquerer of nations, retires

David Beckham, conquerer of nations, retires

For once, David Beckham had nowhere to go. There was nothing left to conquer. Winning in four different countries, this 38-year-old, though still capable, got the chance to depart the game as a winner, on his own terms.

Paris is the last stop of his playing career, after all the success along a trail no Englishman has ever traipsed before. He played for the biggest clubs – Manchester United, Real Madrid, AC Milan – and won the biggest of trophies. Not many players from England like to leave the island behind, and when they do they invariably come back. Not Beckham. He was different. He’ll always be English, and fiercely so. But the moment he left United in 2003, he left as a man of the world, a global citizen, an icon of countries and continents and a brand of companies.

When he arrived in Madrid that same year, he was one of several stars signed by the city’s top club. He joined Zinedine Zidane, Luis Figo, even the Brazilian Ronaldo on a Real Madrid team that should’ve won more than it did. But something else came with Beckham: his marketability. If he could sell enough jerseys, he’d be a success – regardless of how much effort he gave to the cause of actually winning.

Madrid didn’t pretend to be anything they weren’t. They were glitzy, outrageous, cotton candy to the eyes. Image was everything to them, but expectations came and went unfulfilled. After all, these guys were paid to play, and they didn’t even make a dent in their first season together, finishing fourth in La Liga and losing in the quarter-finals of the Champions League.

Four years with Madrid yielded a single trophy for Beckham. He scored crucial goals in that single campaign in which they claimed the league title from rival Barcelona, but in the years leading up to the silver moment, the team made over US$500-million – partly off his appeal. Knowing the size of Beckham’s following in Asia, the club toured China during one pre-season trip. He was a good player, but the ingredients of his fame had stewed all too nicely.

The start of his family’s US$306-million fortune began. He married his wife, Victoria, in 1999, and even before that ceremony they had a son, Brooklyn, whose godfather is Elton John. The movies came out, too, starting with Bend it Like Beckham in 2002. By the time he reached Madrid, he was better served as a celebrity than a footballer. Sure, the good looks caught the attention of women otherwise uninterested in the sport – just as his advertisements in underwear later would – but something else, something within him really coaxed this outwardly side of him.

As a teenager, he dreamt of fame. Not the way a rapper in the projects dreams of it. Money would not be thrown in the air. Beckham understood at an early point in his career the values of power and the greater good that he could achieve. It’s not unordinary to see players participate in charitable events, but he took incredible pride in those things – no matter how big the arrangement. Undoubtedly, he loved the attention, but he loved even more what he could do with it, elevating issues like malaria, HIV and aids to a level no athlete ever before could reach.

Dimitar Berbatov, a former United player in his own right, felt the effect. “If David Beckham says something about HIV,” Berbatov said, “then people will remember it.” All of this didn’t necessarily serve to fulfill some scheme of his. Beckham didn’t take on a life of charity to impress shareholders and agencies. He did benefit from tax breaks, and he didn’t have to worry about his next meal. But Beckham was acting upon this imagined idea of living he had for years: to help, to travel, to bring joy to others and work against the ills of the world. He was born with an active soul, and he had the financial freedom to let it soar.

Some time ago, he even forfeited the right to play with England in an international match. He had made several trips across the globe, and the manager, then Fabio Capello, excluded him from the squad. That’s nothing to take lightly. Playing for his country was the highlight of his career. He made more appearances than any other outfield player for a reason. He always wanted to be there. But he often put his commitment to charities before his football.

Visiting a township near Cape Town, South Africa, Beckham absorbed a new way of life. The people beamed when they saw him, and he shared the same joy. It was easy to connect with the impoverished. Lines of race and wealth and class didn’t appear to him. “When the kids play football,” he told the Times of London after the trip in 2009, “it’s like watching my boys play.”

So if Beckham was an all-star, a huge celebrity, he earned everything. Humility powered his brand. He wasn’t a snob. He wasn’t born out of riches. His mother was a hairdresser and his father was a kitchen fitter. He was a self-made man, full of ambition and endeavour. He was a fighter – the man would not take insults lightly, and he has on more than one occasion challenged fans that cursed at him and demeaned his wife – but Beckham never was an outlaw.

Many resented him because of the celebrity, because of the persona, because of the things we thought we knew about him – especially when he moved to Los Angeles to play with the Galaxy in the summer of 2007. He didn’t leave Madrid for US$250-million, the highly inaccurate figure reported to be the absolute highest possible sum of his initial five-year contract in Major League Soccer. He didn’t leave Europe to be a movie star. He didn’t leave to rest on his laurels in America and slide silently into retirement.

As a 32-year-old, Beckham brought with him to the United States a desire to popularize an unpopular sport in the country. No challenge was big enough for him. This was a leader, a pioneer. Given the chance to be a president or a coach, he would take the former. Beckham was never short of self-belief, and maybe even a little bit of conceit. After all, neither Napoleon nor Hannibal conquered anything without them.

If Beckham thought he could walk the streets of Los Angeles and New York carefree, he was wrong. Photographers followed him everywhere. Hype kept rising, like a space shuttle in the sky, never reaching a crescendo. He did seek all the attention, but it was hard, at times, for him to cope with.

“I think over the years,” he told former teammate Gary Neville in an interview on Sky Sports News, “people have looked at other things. Sometimes that’s overshadowed what I’ve done on the pitch.” There’s truth to that. Most of the time, he was a prop, something to show off, shiny and cool and real. Beckham only had to jog along the sideline to rouse the shrieking masses, to bring thousands in the stadium to their feet. The world’s leaders wish they could inspire with so little effort the imagination and energy of so many.

In his first match with the Galaxy, a summer friendly in 2007 against Chelsea, he hobbled into the Home Depot Center with an ankle injury. Playing wasn’t an option. It was an obligation. He had to. He couldn’t disappoint all the fans. So he put on his cleats, wobbled about, and floundered on the field after taking a tackle to the leg that almost made the whole thing worse. Everyone but him left the field happy, and that was all that mattered.

A millionaire’s happiness likely means nothing to the lot of us, but the man kept his promises and met his responsibilities as a figurehead, a cash cow, a player.

He was always worried about what other people – his teammates, his fans, his employer – thought of him, once holding up an entire team bus to sign autographs for every fan waiting outside. Beckham didn’t want to leave a bad taste in anyone’s mouth. And the rare time that he did, he took the initiative to sweeten the sour.

When he left the Galaxy temporarily in 2009 to play with Milan in a bid to get in shape for the 2010 World Cup, Beckham faced the wrath of his teammates. Landon Donovan, captain of the Galaxy, said Beckham wasn’t a leader. Later, several others didn’t think he was showing enough effort. At one point, Beckham had played more games for Milan and England than he did for the Galaxy.

But then Beckham got injured, missed the World Cup, and proceeded to prove the doubters wrong. This man’s found nothing but motivation in the spotlight. He won his first title with the Galaxy in 2011, and he could’ve left a champion. That first trophy “quieted a few people,” he told ESPN, “which is always nice.” But he decided to stay, at a place where he was adulated and crucified, martyred and defiant. And he won again last year. He won over the Galaxy, he resurrected his image, he left the league as a winner – as he always has.

Things just had to be perfect for him: his passes, his reputation, even the stuff in his fridge. He can’t have too many drinks in one spot. Everything’s got to be in pairs. “I’ll go into a hotel room,” he told ITV in 2006, “and before I can relax, I have to move all the leaflets and all the books and put them in a drawer. Everything has to be perfect.” Victoria calls her husband a weirdo, but he’s a victim of obsessive-compulsive disorder, and his friends sometimes make his life a living hell because of it.

He’s spent his whole life rearranging and matching, placing and scheduling. Once, in Manchester, with Sir Alex Ferguson watching, he stayed on the field long after his teammates left, kicking balls long into the night, one after the other, waiting to hit the sweet spot. Without his obsessions – to be the best, to work hard when talent doesn’t – Beckham wouldn’t have ever scored against Greece; Beckham wouldn’t have ever scored from the centre of the field; Beckham wouldn’t have ever shared such a perfect relationship with the ball. The hair was just right, the looks clean and faultless, the football memorable and decisive.

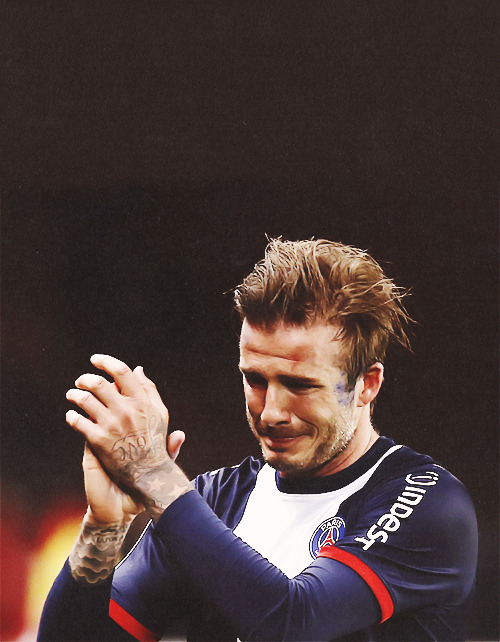

He could probably still play the game. Paris Saint-Germain offered him the chance to continue. But he’s just celebrated a championship with them, the Parisians, the team that gave him one last chance at the highest level. Beckham didn’t take the risk. Instead, he leaves the game without a blemish.

Anthony Lopopolo is an Italian-Canadian freelance sportswriter and a Senior Writer for AFR. He has written for the National Post and the National, and has also made appearances on national radio in Canada and the UK to talk footy. You can follow him on Twitter or send him an email. Comments below please.