Blessed were the cheesemakers: the glory days of Parma

Blessed were the cheesemakers: the glory days of Parma

A couple of decades ago, in a golden age of Italian football, there was a bunch of credible contenders for the Serie A title dubbed Le Sette Sorelle, which translates to ‘The Seven Sisters’. Six of them were traditional powerhouses - Milan, Juventus, Inter, Fiorentina, Lazio and Roma - but one was a team from a place previously best known for its cured hams and cheeses. Step forward Parma Associazione Calcio.

To say the Emilia-Romagna club had little pedigree would be something of an understatement. Serie B was the best they managed in the first 70-odd years of existence with spells in Serie C and even Serie D littered along the way. For a city of close to 200,000 souls, it was a meagre sporting dish to dine from. They would, however, go from famine to feast in the 1990s.

It was a transformation that could trace its roots back to the mid-1970s when President Ernesto Ceresini took the helm. A self-confessed novice in the world of running a football club, he began to build the team’s credentials by what appears to have been - looking back - a process of trial and error. It would take two key appointments to ultimately put the Parmigiani on the road to glory.

In 1985, an ambitious and intense young manager making a name for himself with Fiorentina’s youth team and little Rimini took over the reins with the club still languishing in Serie C1, the old third tier of Italian football. He won immediate promotion to Serie B, and then came within a whisker of taking them to the top flight. However, a couple of memorable Coppa Italia displays against Milan grabbed the Rossoneri’s attention. They plucked Arrigo Sacchi away from the Stadio Ennio Tardini before he could deliver any further impressive results.

Around the same time, however, another vital deal in the Parma story was being signed. Dairy giants Parmalat took over as sponsors and began to pump in funds for a transformation of Biblical proportions. This was now the land of milk and money.

Yet the dreamed-of promotion to Serie A stubbornly refused to arrive. Another coaching revolutionary, Zdenek Zeman, failed to provide the desired effect in a brief reign and the late Giampiero Vitali could not deliver the goods. But a saviour was around the corner, and he spoke with the gravelly tones of the Veneto region.

Nevio Scala, a former player at Milan, Inter, Roma and Fiorentina, had just cut his managerial teeth at Reggina when he was poached for the Parma job. With an already-competitive squad at his disposal, something clicked between club and coach. They would become as inexorably linked as the famous hometown ham and slices of fresh summertime melon - and prove just as mouthwatering a double-act for the Boys supporters group on the Curva Nord.

They set sail towards Serie A together with many of the players who would go on to write great chapters of the club’s history. Spring-heeled goalkeeper Luca Bucci, defensive duo Luigi Apolloni and Lorenzo Minotti, midfield strategist Daniele Zoratto, the man the fans dubbed ‘Il Sindaco’ - the Mayor - Marco Osio and goal grabber Sandro Melli were all part of the squad. But their promotion efforts would be rocked by a pivotal moment in Parma’s history.

On a cold February morning in 1990, news filtered through that President Ceresini’s heart had given way. He was just 60 years old and left a power vacuum which needed to be filled. It surprised nobody in particular when Parmalat completed its “dream deal” to take control of a club which shared part of its name. In hindsight, it was a sliding doors moment for football in the city. Who knows what triumphs and, perhaps more importantly, disasters might not have happened if Ceresini had lived a few years longer?

On the pitch, events of that 1989/90 season were just as dramatic. Having romped through the first half of the season, Parma seemed to suffer a slump around the time of their President’s death. It allowed other clubs to make up ground and leave them with what was effectively a promotion play-off derby with local rivals Reggiana on the penultimate week of the season. The Tardini was packed for the occasion. Goals from Osio and Melli ultimately allowed the players to parade in their underpants to the strains of the Triumphal March from local boy Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida. From a footballing point of view, the place had never had it so good. T

he fate of most neopromosse - newly-promoted sides - in Italy is usually a troubled one. The step up from Serie B to Serie A is a big one and most teams set their sights no higher than gutsy survival. It was pretty much clear from the outset that, having waited about three-quarters of a century to get there, Parma meant business.

Their first season in the top flight brought a remarkable sixth place finish as Scala’s swashbuckling style stunned many of his more illustrious rivals. Foreign stars were added to his squad in the shape of Brazilian goalkeeper Taffarel, experienced Belgian defender Georges Grun and Swedish hitman Tommy Brolin - a more slimline version than Leeds United fans might remember. With the bulk of the promotion-winning side retained, it proved an impressive mix.

But the great leap forward truly came in that tricky second season. Two key players arrived who would become associated more than most with the swagger of Scala’s 5-3-2. Long-haired right-back Antonio Benarrivo and converted winger Alberto Di Chiara at left-back completed his tactical jigsaw. With their marauding runs, they gave the attacking impetus on the flanks which their coach demanded. For much of a match, the Parmigiani looked more like the 3-5-2 being played by a number of sides in Serie A this season.

It brought a first major trophy - the Coppa Italia in 1992 - but more were to follow in an incredible spell. The following year they managed something few would have imagined possible just a few seasons earlier when they were scuttling around in the third division. They were raising a European trophy at a temple of world football - Wembley Stadium.

I was lucky enough to be there on the night they clinched that crown, easily seeing off Belgian outfit Antwerp for the Cup Winners’ Cup. It was a friendly affair, both sets of fans mingling easily, and provoked little interest from locals. From memory, it earned just a few minutes highlights on Sportsnight in the UK. And yet it was an entertaining game, and a big achievement from a side which was clearly going places.

Parma became everyone’s favourite second team. Their football was pleasing on the eye, their players were viewed with jealousy by several clubs and they looked like a role model for building a successful side out of pretty much nothing. They were also refreshingly free of the bitter rivalries that infect much of Italian football. It was a lovely bubble to live in, but it would burst in dramatic style.

But not before more titles were secured. The European Supercup followed their Cup Winners’ Cup success, defeating Milan in the two-legged final. They reached the Cup Winners’ Cup final again - this time losing to Arsenal. Then a UEFA Cup came a couple of years later - once again at the expense of Italian opposition, this time Juventus. Within the space of five years, the boys from the provinces had taken a seat at the top table of Italian football and now had to be considered serious contenders for the Scudetto.

It is not entirely surprising when you look at the level of players the club was able to attract. The more modest signings of the early days made way for bigger names as Parmalat started to demonstrate its apparent financial clout. Colombian speedster Faustino Asprilla, Argentinian utility-man Nestor Sensini and the crazily-coiffured Portuguese defender Fernando Couto were among their acquisitions in the mid-1990s along with Italy internationals like Roberto Mussi, Dino Baggio and Gianfranco Zola. If they were still considered a little side, they were clearly thinking big.

The closest they would come to the league title which was now considered a possibility was in the 1996/97 season, by which time Carlo Ancelotti had replaced Scala at the helm. A teenage sensation called Gigi Buffon had broken through as their goalkeeper and signings like Lilian Thuram, Fabio Cannavaro, Juan Veron, Hernan Crespo and Enrico Chiesa hinted at how seriously they were thinking about a historic Scudetto. They staged an amazing late-season rally to get close to Marcello Lippi’s Juventus but their dream was denied by a couple of points. Not that they had finished with gathering trophies.

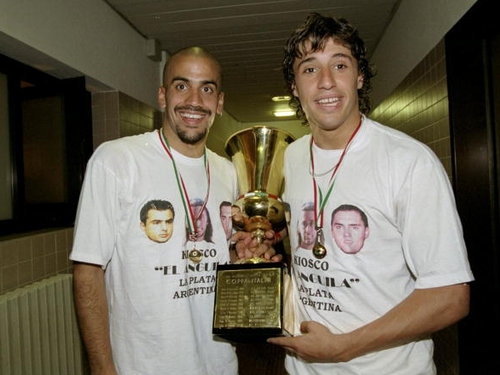

After Ancelotti made way for Alberto Malesani, an Italian Cup and UEFA Cup double arrived in 1999, the Italian Supercup came the following year and, finally, another Coppa Italia in 2002 (under Pietro Carmignani). But the financial storm clouds had been gathering for a while over Emilia-Romagna. There were persistent rumours that Parmalat was in trouble and its financial backing was not worth as much as it had appeared. Like many Italian sides before and after them - the day of economic reckoning was just around the corner.

In December 2003, a multi-billion euro hole emerged in the company’s accounts. Two teams of investigators were ready to look at the books. It became, even by Italian standards, one of the biggest financial scandals of all time. And the football club which had carried the Parmalat name across Europe could not remain immune. Soon after its major backer’s bankruptcy it, too, was in administration. Parma AC were no more - replaced by the newly-formed Parma Football Club.

The collapse on the pitch, however, was not as dramatic as that of the likes of Fiorentina or Napoli. Somehow they managed to hold things together despite having to sell off most of their big names. But they no longer carried the power they once possessed. In 2004/05 they narrowly avoided relegation but a seventh placed finish the following season could not dispel the whiff of decline. By 2008 - after 18 incredible years - they were back in Serie B.

They bounced back immediately and have stayed in the top flight ever since but without ever scaling the heights of that amazing spell in the 1990s. Like so many modern footballing fables, it had been constructed on the most fragile of financial foundations. But it was sure fun to watch while it lasted.

This article is by Giancarlo Rinaldi, an Italian calcio expect and Fiorentina fan who you can follow on twitter @ginkers. He also often writes for Football-Italia and his own tumblr. Comments below please.