The past is an illusion: On Beticos, Sevillistas, and stagnation in Southern Spain

The past is an illusion: On Beticos, Sevillistas, and stagnation in Southern Spain

By John Ray

Over the course of the past six months I’ve spent a considerable amount of time conducting research on both nationalism and market integration in football as part of a long-term thesis project. On January 9th and 10th, I attended both Real Betis and Sevilla’s Copa del Rey matches. The disparate experiences seen in the neighborhoods that house the teams, Heliopolis and Nervion respectively, revealed the lasting effect of the financial crisis on the game and offered a view into the state of the coming years. This micro-level experience fell in line with my macro-level my analyses. First: football responds to the market before the market in economic downturns and slower in recoveries, and second: that regional identities are magnified in times of economic crisis. Oh, and I also had a blast.

My week in Sevilla was a performance piece. I had elaborately designed to evade cultural superstition and sideways glances of nationalistic scorn so that I could see what being a ‘Sevillista’ or a ‘Betico’ really represented to the supporters and the neighborhoods that they represent. I wanted to become an insider, to really see what made these people tick. I stayed the bulk of my time in Nervion where there is no reason for tourists to visit the drab unornamented buildings and spent my time in the gap between tapa and racion. Not a tourist, but definitely not a local. My mission was to be a fly on the wall - I had a great time failing with that as my objective.

My Spanish is not good. It’s not horrible, but certainly not passable. People approached my friend and I before the Betis match, either hoping to start a little chatter about the game or wanting a picture. These comments were mostly met by confusion and “que?”. In the photo-taking incident I actually had a rather nice conversation with a Betico, we talked about the United States, Sevilla, and football; but he almost immediately asked me “eres betico?” with a sense of jovial mistrust, I played along “si, es un mejor club de espana para mi” and he said he had never met a Betico from the United States.

What became clear during my time in Sevilla is that, with the division of the city, the teams are equally a social club as a sporting team. Children and women hang out before the games, belying the typical testosterone based environment that I’ve been accustomed too and my friend’s Nervion host mother, with her knitting needles in hand, was the last person I expected to be a Betico. There isn’t as much animosity between the two factions, either, but your choice seems to be a result of the people that you hang out with, your sector in society, and, obviously, your location within the city. This social context is an excellent cultural barometer of the city and has made the rapidly shifting nature of the game all the more fascinating.

Football in the city changed at some point this summer; the fortunes of its two largest soccer clubs opaquely diverged, as if they were two cruiseliners in the inky dark off the coast of Cadiz or Huelva. Sevilla’s murky financial situation was exacerbated, while Betis continued their steady assemblage of affordable talent. Betis hadn’t finished above 13th since 2004 and Sevilla hadn’t finished below 9th since they were relegated in 2001, yet here we are. Betis are 5th in the table halfway through the season and Sevilla are in 12th, 9 points off their local rival.

The tension between Sevillistas and their club is evident, while the Betis supporters seem absolutely behind their club. Before the Sevilla match in Nervion the streets were absolutely flooded. The supporters swarmed around the Sanchez Pizjuan stadium and began a race to the bottom of their numerous Cruzcampo 40s, cigarette butts, and blunt roaches 15 minutes before the match. 5 solitary policemen in riot gear strafed through the crowd without much intention. The experience of this en-masse volatile substance consumption was rather surreal, but what was even less believable was the lack of both fans and passion inside the Pizjuan. I could have sworn that there were 2 or 3 times as many people in the streets as in the Stadium. The upper tier was almost completely empty and, save for the first 15 minutes, the supporters were rather subdued in song.

The match was unremarkable and meaningless, Mallorca ran out 2-1 winners, but had lost the first leg 5-0. In the comparable situations I had attended, notably a rocking match at Espanyol against Rayo last year, the supporters used the match as an excuse to party, but despite the Sevillistas promising start in warm-ups it didn’t seem they were in a mood for a party. Maybe it’s understandable for a team staring at the bottom of the table and faced with selling its best players. In the 75th minute (what appeared to be) the visiting Las Palmas players marched to the exit and were given the loudest ovation of the night, this was the only time I felt the inter-city rivalry was truly palpable while I was there. After the match four city blocks would be swathed in beer and hose spray, it’s hard to say which was which. I didn’t taste.

The next night in Heliopolis, on the other hand, was rowdy from start to finish. The streets were lined with palm trees, mansions coated the path to the match from el centro, and the young fans all hoisted their scarves high. The Betis supporters might appreciate the rich veinof form the team is more than most, because they had been so disappointing in previous years, but this season they have taken a defense led by £650,000 worth of 3 new recruits, moved up to 5th in the table, and comfortably through the Copa del Rey. One reason is the sparkling play of Benat and Joel Campbell (on loan from Arsenal), but it seemed like the player Beticos most identified with was the diminutive striker Ruben Castro. Castro, 31 and ironically a Las Palmas academy graduate, seems to be held by the supporters as a symbol of the club itself: a fun, scrappy, “underdog”, who has a genuine spirit about him. When he started warming up to replace Pozuelo in the 35th minute adulation was showered on him from all angles and the roof came off the building when he grabbed the winner in the 85th minute.

Both teams have become financially threatened by a combination of La Liga’s top down revenue sharing structure, the global economic crisis, and the threat of wavering local support, but, while Sevilla has largely collapsed, Betis offers a path forward. The sale of two of Sevilla’s top two players, Negredo and Rakitic seems inevitable at this point. They can’t afford to continue paying their wages and need the transfer fees to balance the books. The sale of these players will be traumatic for supporters because they are fantastic and skilled, but also because they have grown to represent a golden age of the club. In the Pizjuan, Rakitic received an enormous amount of praise from the supporters before even setting foot on the pitch and was lauded every time he touched the ball, while 19 year old Kondogbia, who was my man of the match and played some unbelievable passes, hardly received a reception at all. It seems like Sevillistas are unable to appreciate the present as they are living under the shadow of a more successful past, but without their support in transition the club will not be able to move into a sensible future. The times of excess in Nervion are gone and a strategic restructuring seems necessary.

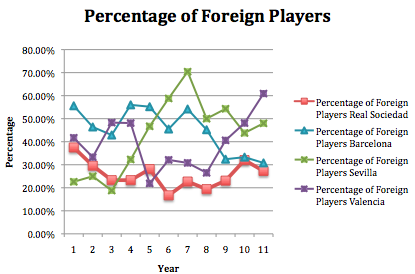

Perhaps it is because the team effectively represents Seville as a city to the football world (much more so than Betis), that change has come so hard. My research of the past decade in Spanish football indicates that in times of financial success, Sevilla has chosen to import expensive foreign talent, while in times of hardship, they resort to using more domestic and, specifically, Andalucían players.

This model operates in stark contrast to Valencia’s model of using the international market in times of financial hardship to look for bargains at a broader level. One theory I have to the nature of these models is that the fans support Spanish players at a higher level and Sevilla, like most sports organization is driven first and foremost by ticket sales and merchandise. However, that approach, while possibly beneficial from day to day, seems shortsighted as nothing drives revenue more than a successful team and relying heavily on a small market (in the context of the entire world) handicaps their success.

Betis was able to construct their team at present without the shackles of success to prevent them from tinkering with different cheap options and finding a tactical combination of players that was successful. 3 of their 4 starting defenders were purchased this summer for a combined fee of £660,000. Paulao and Angel Lopez were free, while Polish international Damien Perquis cost the fee. Betis are living in the moment, which seems to be the source of their success. The players defenders were all battle tested at the age of 30, 31, and 28 respectively.

Instead of constructing a side for the future in this age of Spanish impermanence, they have opted to use loans the free transfer market and have been more successful than Sevilla at a fraction of the cost. Their signing of Ruben Castro in 2010 embodies the mentality of the team more than anything else. Castro was considered “past-it” at 29 and was certainly a less-sexy option than many because of his diminutive stature and massive loan history. Castro was purchased for a meager €1.7m and has gone on to score 53 goals since the move.

The past is an illusion that Spanish clubs and their supporters need to stop living in. Betis have constructed a side that will be successful in 2012 and are successful because of it, more Spanish teams should follow their advice or they too will fail. The economic crisis has rendered Spain a shell of its former self in the areas hit hardest by the collapse, but the Spirit of the people is still there. Beticos and Sevillistas drink the same Cruzcampos fifteen minutes before kickoff, but their clubs are heading in different directions and not because of the financial crisis, but because of how they chose to respond to it.

This piece was written by John Ray, a senior writer for AFR. You can follow John on Twitter here. Comments below please.