Euro 2012 History of the Hosts: Ukraine

Euro 2012 History of the Hosts: Ukraine

Poland and Ukraine: the unlikely duo. This is the second of a two part series by John Ray on the history of Euro 2012’s respective hosts, allowing fans to become familiar with the two nations that will soon be placed under a microscope. Read part one here.

The idea of anything being a solely Ukrainian enterprise was barely being conceived twenty years ago. The country had, after all, just ended an 80 year long relationship in which all decisions from (the capitals) Kharkiv and Kyiv came from Moscow. Ukrainians have a saying “a hungry wolf is stronger than a satisfied dog”; it is emblematic of the culture that has been produced by decades of necessary survivalists under the harsh realities of Soviet life. The people of the Ukraine have had to fight for their rights, food, and land as they have been repeatedly tread on the path to and from Russia. While the Poles were able to gain their liberation after World War II, the Ukrainians had no such luck; they were controlled by the Soviet Union after the Peace of Riga in 1922 and only gained their own sovereign territory after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1991.

Now in the era of Ukrainian independence things are getting better, but slowly. There is still corruption and controversy, ex-prime minister Yulia Tymoshenko is currently being jailed and there are photos of the bruising from her being (allegedly) beaten in prison. Football has always been a way for the country to come together and embrace play over a bleak outlook, there is a stereotype of Ukrainian efficiency in sport (that was developed by the Kiev teams of the 70s and 80s), but the new players and teams are as enjoyable as efficient and have become a real joy to watch. Euro 2012 will either place the building blocks for the countries continued success, or quickly leave them as learning spectators at their own tournament.

The history of Ukrainian football began at the end of World War I, when football had finally spread to almost all of Europe. The first “pan-Ukrainian” football competition began in 1922, where teams from around the area entered a provincial championship in order to qualify for an All-Soviet championship. When teams from the province competed it was always an intense affair because of the games potential to act out local rivalries, but after the champion was selected there was a feeling interesting admiration towards them as the territory’s representative. The victorious teams genuinely became regarded as the Ukrainian national team for that year, because they emblemized the football being developed in the province as a whole.

Early on the amateur team of Kharkiv, the capital city at the time, was dominant. They won 8 of the first 10 championships and bore the standard for Ukrainian football. This continued until the mid-1930s when two factors, the Soviet league professionalizing and the capital shifting to Kyiv, dramatically altered the locations and importance of football in the country. Dynamo Kyiv was the only Ukrainian team introduced as a permanent member of the Soviet top league, a move that came to symbolize the shift away from Kharkiv in both politics and sport.

World War II was devastating to the Ukraine. The country was stuck between a harsh Soviet rule and the unknown menace of the Nazis and was treated as a mere territorial pawn in a broader conflict. Football ground to a halt, but amateur competition continued as a means of incorporating play into the bleak life of occupation. The story of Dynamo’s “Death Match” although often exaggerated, is exemplary of how the club came to maintain a silent, but powerful, nationalism in the face of adversity. During Nazi control of the Ukraine between 1941 and 1943 many members of the Dynamo side continued to play Amateur football for “Start” and were gaining local press for their magnificent performances. Challenges came in from many teams and they set about consummately defeating a few German and Hungarian teams on the pitch. These defeats began to humiliate the German officers who considered themselves indefatigable and, after Start defeated the best Nazi team in the area, the Gestapo quickly swept in to arrest many of Start’s best players. This culminated in the Nazi forces cruelly torturing them and/or sending them to the Syrets labor camp in a cruel turn of fate. It was a precipitous and terrible fall for the Dynamo players who were the cream of the country not too long ago and showed just what lengths the German’s would take to regain their pride. This defiance in the face of a hegemonic force was adopted by Ukrainians as a symbol of the will of their nation and they have embellished the story over the years elevating it to the point of folklore.

As the rubble of World War II and its devastating effects on both Ukraine and Russia ameliorated, the leagues slowly returned to cultural prominence. Dynamo Kyiv was, again, the only team included in the Soviet league for a couple years, but then more and more teams became included to the point where the top five Ukrainian clubs all became major players in the League at some point. These five-clubs all came from the separate metropolises of Kyiv (Dynamo), Donetsk (Shakhtar), Kharkiv (Metallist), Odessa (Chornomorets), and Dniprpetrovsk (Dnipro) and began to represent regional ideologies within the Ukraine. This formation of identity around a football club also maintained a unique local loyalty that superseded the supporter’s Soviet loyalty. Football in the Ukraine steadily grew until the 70s and 80s where Dynamo represented a seismic shift in the competition and club football at large.

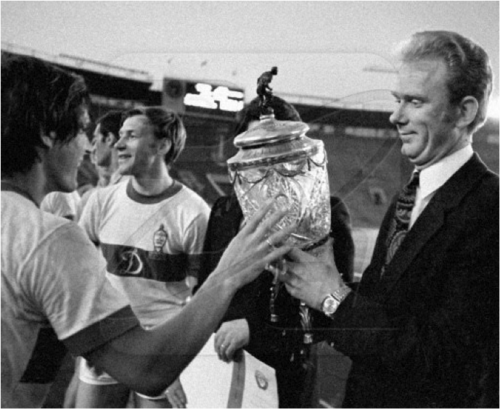

The teams that won the Cup Winners’ Cup in ‘75 and ’86 employed statistical analysis and a focus on reducing errors through scrupulous review until the team could play “zero-error football”. The manager of Dynamo, Valeriy Lobanovskyi, preached a form of tactical evolution that was predicated on utilizing players as more than a zero-sum game, but combining talents in order to create a net-productivity greater than a team’s parts. It has been long known that all great teams have this collectivity in play, but Dynamo’s side was the first to actively try to reach it through scientific methods. The club won the soviet league 8 times in its final 25 years, a huge achievement for a Ukrainian team and their dominance continued until the fall of the Soviet Union and the departure of Lubanovskyi who moved on to manage in the Gulf (UAE and Kuwait).

The collapse of the Soviet Union in the Ukraine has been most defined by the emergence of the free market and the rise of a national identity. In football this was manifested in new challenges to Dynamo and the emergence of the national team as a rallying point for sport in the Ukraine. Kyiv’s dominance was thought to continue when the new Ukrainian league began as they had retained players from the Soviet era and had funds to match their success. Cracks in the armor of a team protected by the Soviet system quickly appeared, though; in 1992 unheralded club Tavriya Simferopol won the first Ukrainian league championship against all odds, emphasizing a newfound unpredictability in the league. Shakhtar also slowly gained steam throughout the decade and the Donestk side’s ascent to the top reached its culmination (similar to Chelsea) when ownership was passed down to billionaire businessman Rinat Akhmetov after the assassination of the previous chairman, Akhat Bragin, in 1995. Shakhtar, would, after a period of second-bests and cup success in the 90s, finally get reward for their tremendous investment with the victory in 2001-2002 and 5 of the next 9 championships. Their victory over the instantiated elite spoke to the power of new money to challenge dominant paradigms in the Ukraine. Parity was now quickly being accessible through the mechanisms of market selection instead of ruling elite favoritism (as seen with Kyiv and the Moscow teams in the Soviet league). There is still systemic inequality in that none of the teams can really match the spending power of a billionaire, but money has always been easier to challenge than class.

The development of the Ukrainian national team was rather steep after its 1994 debut in international competition. While the success of club football in the country obviously provided a launching point to quick success, it is still rare to see a team reach the quarterfinals of a World Cup after only existing for 12 years (as the Ukrainians did in 2006). The quick transformation from nothing into contenders can be attributed to the experience that many players and staff members had as integral cogs in the Soviet team and the choice of key players like Andriy Shevchenko and Serhiy Rebrov to declare for the country instead of Russia like some of their compatriots (Kanchelskis and Onopko). It was not if international football was an oddity to the side, Ukrainians comprised 9 out of the USSR’s 11 starting lineup members at the Mexico ’86 World Cup and, if a greater amount of players had carried over, the national team would have probably hit the ground running even faster and qualified for some more tournaments.

The current Ukraine team has enough quality to deceive the limited expectations that they have received. Liverpool castoff Andriy Voronin looks to be the teams target man, but has been is poor form in the lead up to the competition and experienced goal-scorers Andriy Shevchenko and Artem Milevskiy could figure prominently as replacements or substitutes. The other players that could provide stardust to the side are Andriy Yarmolenko and Oleg Gusev (who has been in brilliant form). The Ukrainians are certainly more than capable going forward as seen in the run-up, but they have a very shaky defense that will most likely be their undoing. Tymoschuk and Rakitskiy are the only “big name” stoppers and the team has given up 5 goals in its past 2 friendly matches, thus, it is hard to imagine the yellow-blues making it out of a group with France and England, but one should expect some large scorelines. A third or fourth place group finish is what should be expected of the Ukrainians, but they could hypothetically place second if there is an English or French collapse (not out of the question) and they perform better than the Swedes, “stranger things” always happen at the European Championships. It’s unfortunate for the Ukraine that they got placed in such a difficult group, crashing out in front of one’s home support is always a very painful experience, but seems to be the most likely result.

This article was written by John Ray, a recent graduate of Pitzer College. You can follow John on twitter here. Comments below please.