ASEC Mimosas: Ivory Coast’s Football Factory?

ASEC Mimosas: Ivory Coast’s Football Factory?

By John Ray, follow on Twitter.

“Les Elephants”, the footballers of the Ivory Coast, help captivate and enthrall a nation while playing against Madagascar: large outdoor television flicker and the metropolis of Abidjan rustles. Arouna Kone (PSV) crosses to Salomon Kalou (Chelsea) at the edge of the area; the supporters swell in deliverance as he belts the ball into the Malagasy net. There are chants and dances to the djembe drum in the stands and in Abidjan; life in the country is good. A month later the stadium is empty, except for a smattering of people around the halfway line. ASEC Mimosas, the Ivory Coast’s most successful team, are playing a match, but no one seems to care. Ivorian international football has always had the capacity to unite and excite the nation, but interest in domestic football has gradually shrunk to null as the push for Europe has consumed the clubs. ASEC and its academy provide a perfect example of the effects (good and bad) of what is, for the lack of a better term, player commoditization.

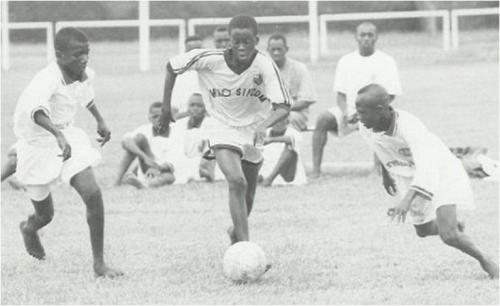

In 1993 Jean-Marc Guillou founded Academie de Sol Beni as the reserve team for ASEC Mimosas with the explicit purpose of educating players and setting them up to move to Europe. The club, in the heart of Abidjan, has come to represent a massive chance for young Ivorian footballers to achieve an altogether more glamorous life, evidenced by the academy’s “Philosophy of Work”: ”a 17 or 18 year old player has a great opportunity playing in the African Champions League as it is the competition most watched by foreign clubs (translated).” This outspoken objective of developing players as exports has proven to be successful and produced many stars (the Toure brothers, Kalou, Gervinho, and Romaric) from the “crown jewel” of African academies. The rigor of the program helps partially explain why the club has produced so many top players. Tutelages train two times a day and are up working on either school or football from 6:30 AM-8:30 PM learning how to become a better professional. The club focuses on scouting mentality then working on aspects of the game that can be more easily taught. This idea lies at the root of the intensive training and creates an atmosphere where players learn collaboratively instead of constantly competing to prove themselves. Within 5 years of implementation this youth philosophy paid huge dividends, as some of the first products of the academy led ASEC to win the African Champions League. European scouts caught on and began putting in transfers for young players. They have not been to the finals since.

The football export industry is not all sunshine for the players either. The divergent fortunes of Ivorians sent to Europe became apparent when Guillou transferred 14 members of ASEC to play for (his new club) Belgium’s KSK Beveren in 2003. This link was supposed to be good for the players and the club, giving them European experience and a better platform to succeed, but it has retrospectively symbolized the exploitation of young players as for personal gain. Gulliou’s vision for personal success brought teenagers to a continent they have never visited as (comparatively) low-wage workers and expected them to sink or swim at a small team in Belgium. The move had numerous successes: Gilles Yapi Yapo, Romaric, and Eboue all became big hits in Europe shortly after, but the failures were left by the way side and expected to adapt in a country 7000km from home without the financial resources to go back to the Ivory Coast.

The story of Mohammed Diallo tells a more “typical” turn of events: After playing for Beveren for three years he was sold to FC Sion and then loaned out to an Israeli club. 2 years later he was out of contract with Sion and played in the very lowest French leagues before going all the way back to Africa to play for Ajax Cape Town as a 26 year old. The immense pressure of knowing that an opportunity might be your last surely crumpled many players, but many were just not ready to move away from home at the age of 17. The harsh reality of football quickly set in for many of the young elephants.

The question then becomes: Whom or what does sending players abroad benefit? Other than the players who make it and the clubs receiving them it is really hard to say. In theory the transfer money should be reinvested and make Ivorian football better, but with a demanding schedule and low attendance much of the return is needed just to maintain upkeep. If ASEC Abidjan could draw even half of the Houphouet-Boigny stadium (with a capacity of 35,000) they would not have to rely on transfer fees and would be able to retain some players and improve the product. The demise of the domestic league is cyclical, but it seems to be accepted as a harsh reality of sport in the developing world. The lure of quick money has again triumphed over long-term gains. In an interview with BBC, ASEC coach Xavier Minougou stated, “If Europeans have more money and come and buy our players, I think it’s good for Africa.” Practice has proved this to be incorrect. In keeping many of its best players, the South African premier league has been able to attract comparatively massive crowds and bring in players from all around Africa. If ASEC could retain even a few of their immensely talented players (wonderkids Wilfried Zaha and Abdul Razak trained at the club) things might begin to change for the better. As it is they are stuck in the paradox of football in the developing world: as more talent is sold, domestic football becomes worse.

John Ray is a recent graduate of Pitzer College in California, where he studied Political Psychology. He also writes about the beautiful game on his Tumblr.