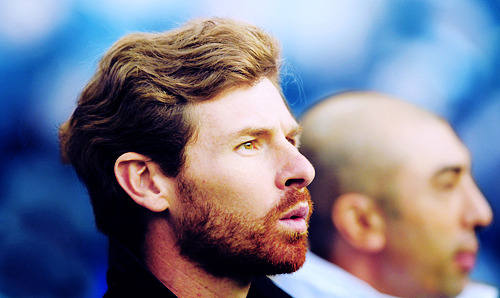

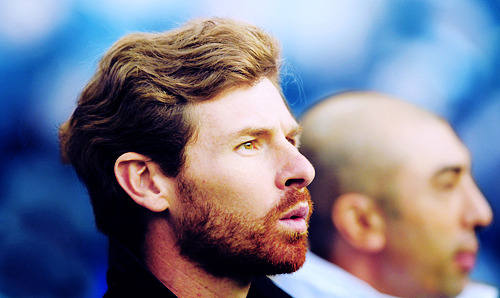

André Villas-Boas’ Philosophy of Composition?

André Villas-Boas’ Philosophy of Composition?

By Josh Clarke

On initial inspection, similarities between Andre Villas-Boas’ Chelsea and Edgar Allan Poe seem most abundantly clear in a shared propensity for an excruciating and painfully drawn-out narrative (think Fernando Torres and The Pit and Pendulum). Push your luck a bit further and I could be persuaded to believe that a real, defensively-capable John Terry could be found in an Oval Portrait somewhere deep within Cobham.

Yet and perhaps least harrowing for Chelsea fans, could be the suggestion that Villas-Boas’ time at the helm at Stamford Bridge could be viewed a great deal more positively through the lens of Poe’s Philosophy of Composition.

Written as an exposition on how a poet achieves a powerful end effect, the essay lists the practices involved in the configuration of the poem The Raven. Leaving aside the distracting suggestion that the most poetic topic conceivable is the death of a beautiful woman – though an examination of this and Ashley Cole could well be saved for a rainy day – the basic premise is that a great piece of literature will be achieved through methodologically working back from a predetermined end point.

“Nothing is more clear than that every plot, worth the name, must be elaborated to its dénouement before anything be attempted with the pen. It is only with the dénouement constantly in view that we can give a plot its indispensable air of consequence, or causation, by making the incidents, and especially the tone at all points, tend to the development of the intention.”

For both Villas-Boas and Roman Abrahmovic, this dénouement was observable all last season at Estádio do Dragão, with Villas-Boas’ Porto side playing the type of football – one not even achieved by Jose Mourinho – that the Russian oligarch has hankered to see since buying the club.

Villas-Boas time at Porto was illuminated by a series of eye-catching records as the club romped gleefully to an unrivalled treble. The Portuguese usurped Jesualdo Ferreira after an underwhelming 2009/10 campaign saw Porto finished 3rd in the Primira Liga yet the side’s fortunes were changed by a couple of key factors which saw Villas-Boas transform the side to one capable of sinking 145 goals in 58 outings.

First up was the departure of two key midfielders – Raul Meireles and Bruno Alves. In parting, the duo – who had been embedded in the centre of the Porto midfield for the best part of half a decade – allowed Villas-Boas to fiddle with the mechanics at the heart of the side. The midfield Ferreira’s 4-3-3 was essentially flip reversed, with one of the two usually deep-lying players given license further up the pitch. With Villas-Boas, Fernando sat deep, with Joao Moutinho and Fernando Belluschi or Fredy Guarin free to join the potent front three. This fundamental shift in attacking philosophy was accompanied by an aggressively high defensive line and relentless pressure in the opposition half.

Fast-forward to Villas-Boas at the Bridge and it quickly became clear that the immediate implementation of this system was a primary objective. An objective that wasn’t fully abandoned until they were outduelled 5-3 by Arsenal team hell bent on punishing the Chelsea back four’s inability to defend adequately so far away from Petr Cech. An objective that has, admittedly, come nowhere near even partially realised.

Since that sticky patch Villas-Boas has tinkered with variations of 4-3-3 and 4-2-3-1 and adopted a deeper-lying defensive line reminiscent of Mourinho and his many successors in the need for short-term stability. The Porto system though, is evidently still an idyll the team is geared up towards emulating and Villas-Boas seems be working back from that grandiose punch line to the predicament he currently finds himself in.

Overhauling a team that still bore all the defining characteristics – both in personnel and style – to Mourinho’s Premier League winning side of 2004/05 is the biggest on-going challenge Villas-Boas faces, particularly given the contrast between that particular team’s ruthless pragmatism and the panache Villas-Boas wants to recreate. For the first time since that period, through the teams of Avram Grant, Luiz Felipe Scolari, Guus Hiddink and Carlo Ancelotti, the current Chelsea side is beginning to take on an unfamiliar look – even if an assortment of Terry, Cole, Frank Lampard, Didier Drogba or Petr Cech are fielded. Ramires, Meireles and Oriol Romeu are establishing themselves in the middle of the park in a setup not too dissimilar to Porto circa 2010/11. Likewise Daniel Sturridge, Juan Mata and Fernando Torres, in theory though nowhere near in practice, represent a trident with similar distinguishing features to that of Hulk, Falcao and Silvestre Varela. That Chelsea front three will click, at some point.

The acquisition of Gary Cahill, as aptly demonstrated here by Michael Cox of Zonal Marking indicates Villas-Boas’ hunger to reinstate the advanced rearguard that was tried, tested and abandoned earlier in the season while, whether drawn out by the style of Swansea, evidence of a high tempo pressing game within the opposition’s final third, was visible midweek. It was interesting to note that after going 3-0 up against Manchester United, Chelsea retreated back into a shell, defending from deep while attempting to smash and grab on the counter. It was a regressive step that proved disasterous.

Regrettably, these things will take time to implement, especially without the safety net provided by the guarantee of immediate success.

The frustrating thing for Chelsea fans is that club’s exasperating yet necessary evolution under Villas-Boas is a disagreeable contrast to the remarkable revolution undergone at Porto. It must be comforting to know that the Portuguese has a previously-realised zenith from which he’s presently working back from.